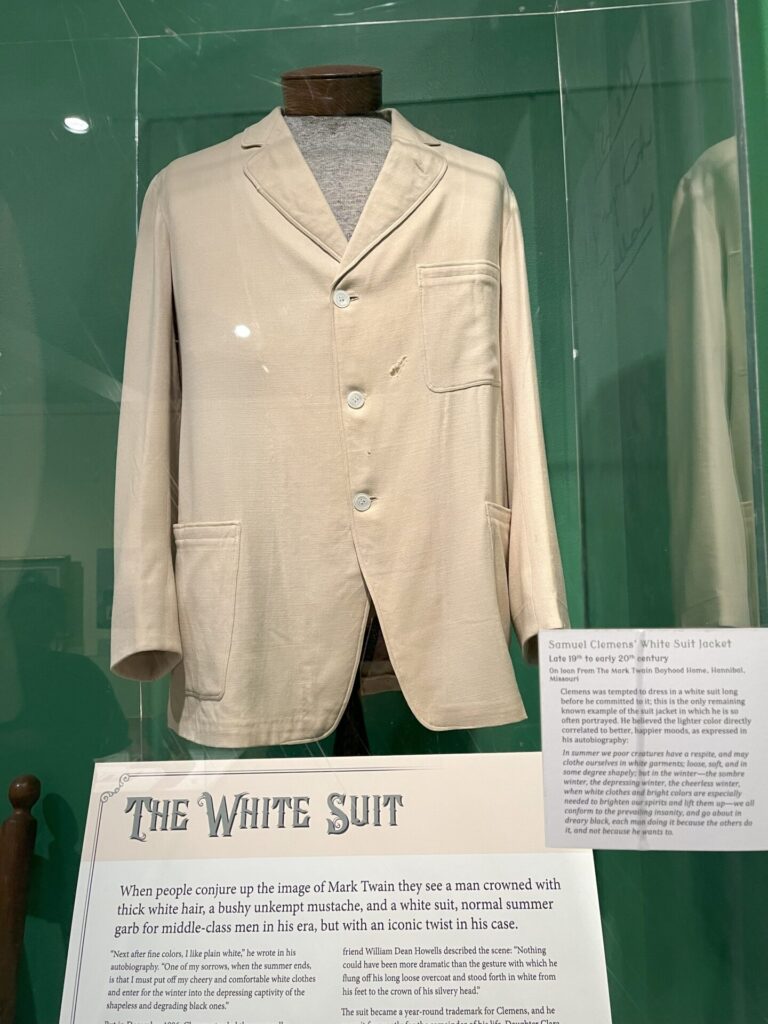

He was a man of many tastes, opinions, and contradictions. He hated the invention called the telephone, despite a life devoted to the written and spoken word. Later in life he proudly wore an unusual, loud white suit he called the “dontcareadam” ensemble. One of America’s most gifted literary figures, he was never shy about expressing his strong opinion in a vigorous, articulate way.

We need people like him more than ever today.

Born as Samuel Langhorne Clemens in 1835 and known as author, humorist, speaker, essayist Mark Twain for most of his life, the Missouri native remains one of our nation’s most revered storytellers and observers of life. His knack for expressing forceful opinions and observations is sadly lacking during the turmoil of our early 21st century.

Who will be our Mark Twain of 2025, knifing through the cloud of social media blathering, wildfire-like spread of misinformation, weak-kneed journalism, and political lies? Who will help us better prepare for the oligarchy taking shape in Washington, D.C.?

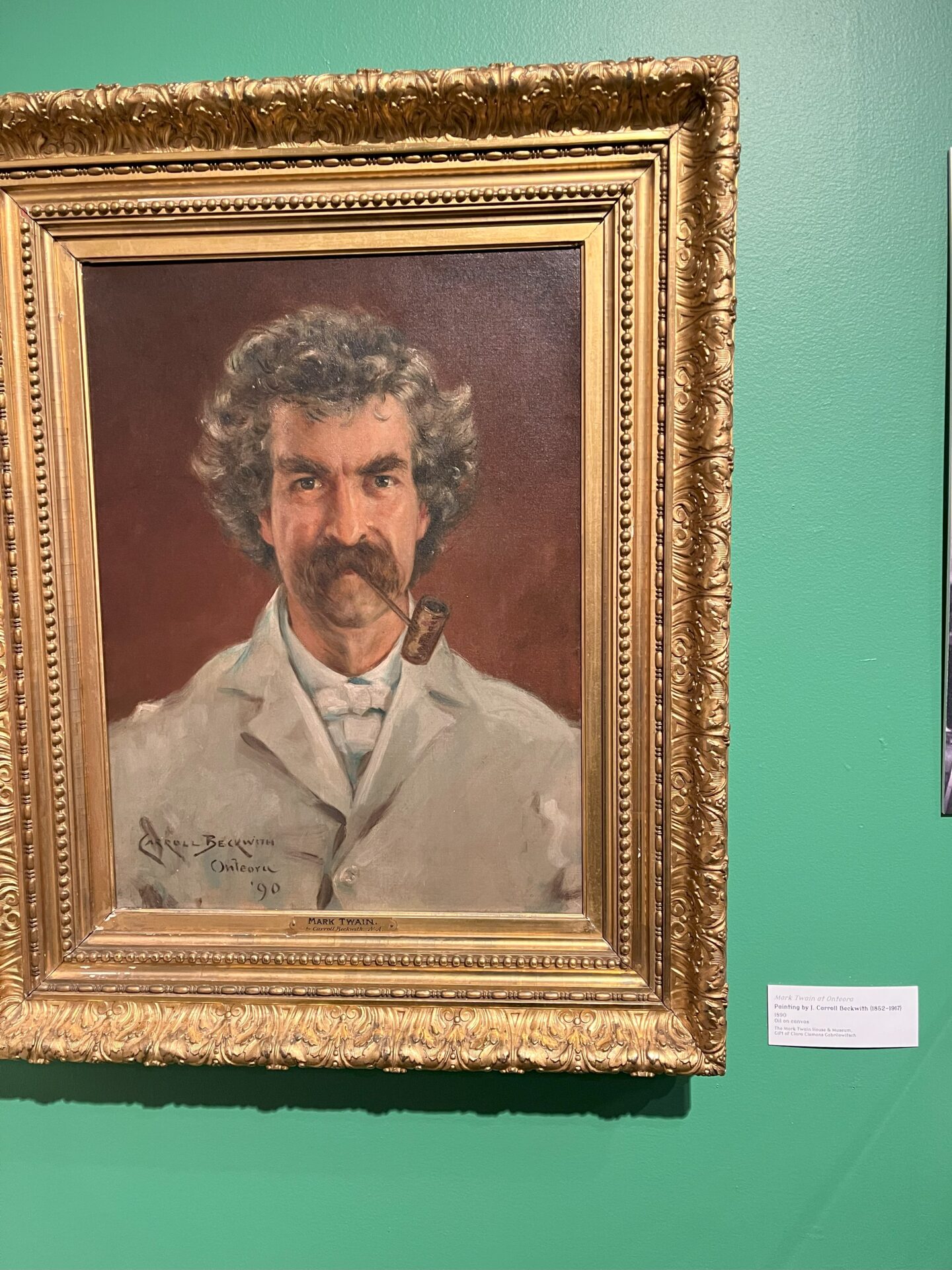

Our libraries, bookshelves, museums, and other historical storehouses are filled with evidence of the trail blazed by Twain over his 74 years. Academics and researchers have spent decades studying the man and his writings, expanding our understanding of who he was, and what he represents today. His impact on our lives was so great that a Hollywood star, Hal Holbrook, made a career out of impersonating Twain in humorous “lectures” given around the world and broadcast to millions. With so much information, it can be difficult to form our own portraits of the man. An easier way would be to visit the home where Twain and his family lived for 17 years, especially if you live in the northeastern U.S.

Situated on a small hill just off Farmington Avenue in Hartford, Connecticut, Twain’s 25-room, three-story house was completed in 1874 as the nation wrestled with Reconstruction and the lingering issues of the Civil War. Twain often said his 17 years spent in the house were among his most enjoyable and productive. But in 1891, Twain, his wife Olivia (Livy), and their three daughters moved out due to financial problems, some of which were related to the writer’s failed business ventures.

The family sold the property in 1903. After changing hands several times, the house was acquired by a nonprofit organization in 1929 and later named a National Historic Landmark. It was even used, for a time, as an apartment building. After years of restoration the Mark Twain House and Museum opened to the public in 1974. It has continued to evolve since then with the addition of a museum/welcome center and other facilities. Thousands visit each year to learn more about the complex man who gave us stories like “The Prince and the Pauper” and “Life on the Mississippi.”

Visitors to the house are only allowed in through guided tours, led by experienced, engaging historical interpreters. On the day I visited in late 2024, I learned from guide Stephanie Silver that no photographs are allowed, but I felt fortunate to wander the well-preserved halls, stairways, bedrooms, and other places in the home designed by famous architect Edward Tuckerman Potter.

Much of the furniture, fixtures, and other items located throughout the 11,500-square foot building are original to Twain’s residency or represent objects found elsewhere but manufactured and used in the late 1800s. The museum’s curators have gone to great lengths to present the home as it appeared when Twain and his family, butler, and other helpers lived there. I loved the expansive first-floor library, featuring shelves stocked with books, floor-to ceiling windows, and plush, upholstered chairs, where Twain spent hours reading or telling stories to his children. The library opens to a beautiful conservatory/greenhouse with walls of windows and thriving plants.

My favorite room was what today would be called a “man cave.” Twain’s billiards room on the third floor was the site of hours of discussions—mostly among men—pool contests, and choking cigar smoke. The room is an important part of the house tours because it’s where Twain wrote many of his works. He even used the billiards table to spread out pages for editing. I let my mind wander as I considered the fact that I was standing in the room where Twain crafted all or parts of “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” and “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.” The room literally reeked of literary mastery. Like many of the other rooms in the house, the billiards room features a large fireplace. An outdoor porch provides stunning views to the west and perhaps a chance to inhale some clean air after a spirited discussion or billiards game. Throughout all the rooms, the main physical characteristics are wood walls and floors.

An amusing anecdote from guide Silver involved Twain’s bedroom on the second floor. Twain so loved the large, intricate headboard that he often slept with his feet against it so he could admire the headboard as he nodded off to sleep at the opposite end. And that newfangled telephone gadget? Twain simply felt it was an annoying device that only provided interruptions. He rarely used the phone in the kitchen, preferring instead to communicate by writing. On the rare occasions he talked on the device, they were short conversations, Silver said.

***

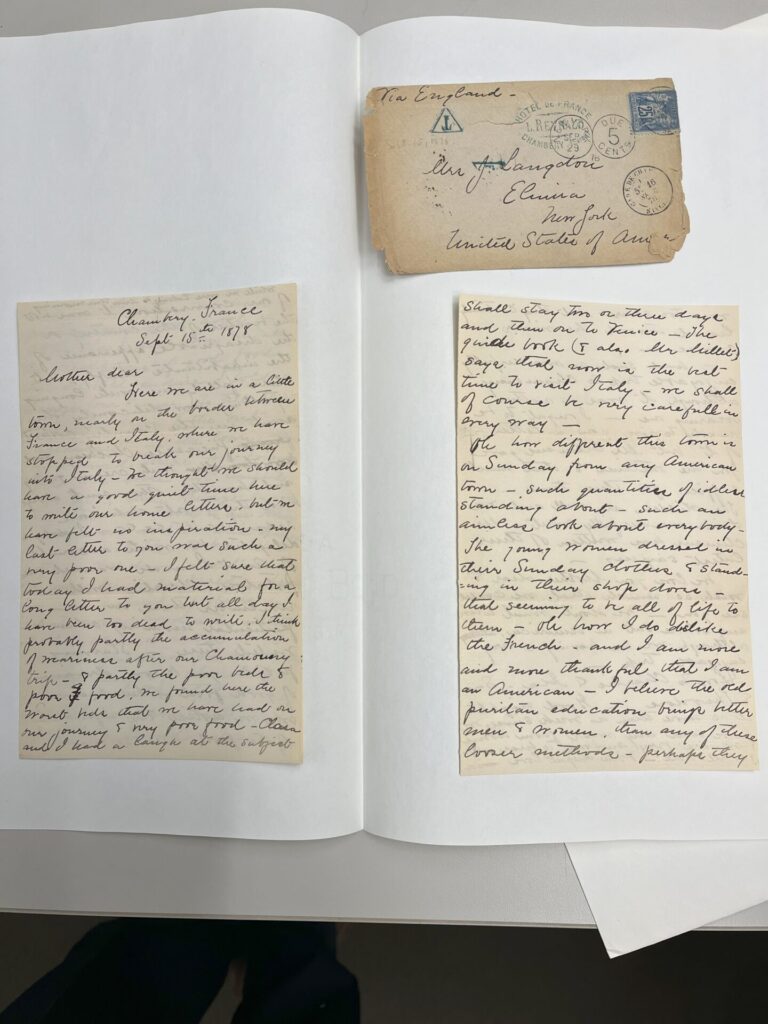

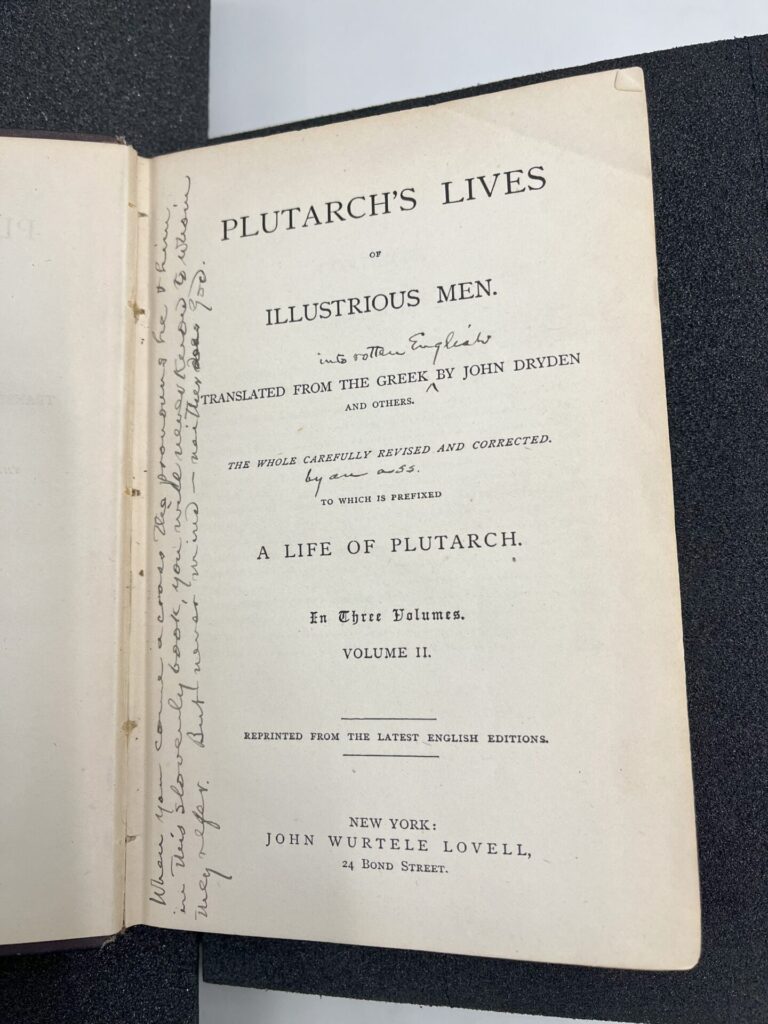

After the one-hour house tour, museum Director of Collections Jodi DeBruyne invited me to see some private collections in the museum adjacent to Twain’s house. Artifacts ranging from personal Twain items to handwritten notes to artwork are stashed amid rows of tall, moveable stacks. Three items stood out.

Written in southern France, a September 15, 1878, handwritten letter on parched, yellowed paper from Twain’s wife Livy to her mother, Jervis Langdon, in Elmira, New York, contained stories about the the famous couple’s European travels. They had stopped in Chambéry near the French border with Italy and were poised to travel on to Venice.

Perhaps apologizing for the mundane letter she was crafting, Livy wrote, “We thought we should have a good quiet time here to write our home letters, but we have felt no inspiration.”

DeBruyne also showed me an example of Twain’s handwritten comments, and sharp opinions. In an old copy of the book “Plutarch’s Lives of Illustrious Men,” Twain scribbled some notes on the cover page, warning readers about the … “rotten English … ” employed by translator John Dryden. Twain expanded in a note he left near the binding on the same page: “When you come across the pronouns he and him in this slovenly book you will never know to whom they refer. But never mind—neither does God.” Yes, Twain was quite the literary critic, among his many other skills.

One final item was an unexpected treat. When he passed away in 2021, actor Hal Holbrook donated to the museum all the costumes and props he used during his over 2,100 performances as Mark Twain. DeBruyne said she and her co-workers were still cataloging and curating the materials. She pulled out one small box and removed several flesh-colored pieces of rubbery plastic. They were the prosthetic noses Holbrook used as part of his overall effort to look as much as possible like Twain. “Along with eyebrows, wigs, his clothing and other parts of his stage outfit, these represent yet another way to remember Twain, as well as those who helped widen awareness of him,” she said.

***

Before leaving, I asked DeBruyne what she felt most visitors take away from a visit to Twain’s family home. “I feel they come here looking for Mark Twain and they leave with Samuel Clemens,” she said. “They get to see how he lived, that he was married and had a family. They leave with an impression of the real person he was.”

***

The Mark Twain House and Museum is located at 351 Farmington Ave., Hartford, Connecticut. The phone number for the facility is 860-246-0998. It’s open six days a week from 9:30 a.m. until 4:30 p.m. The facility is closed on Tuesdays. Visitors waiting to take a scheduled tour inside the house can wander around the Visitor Center in the museum and view a film about Twain’s life.