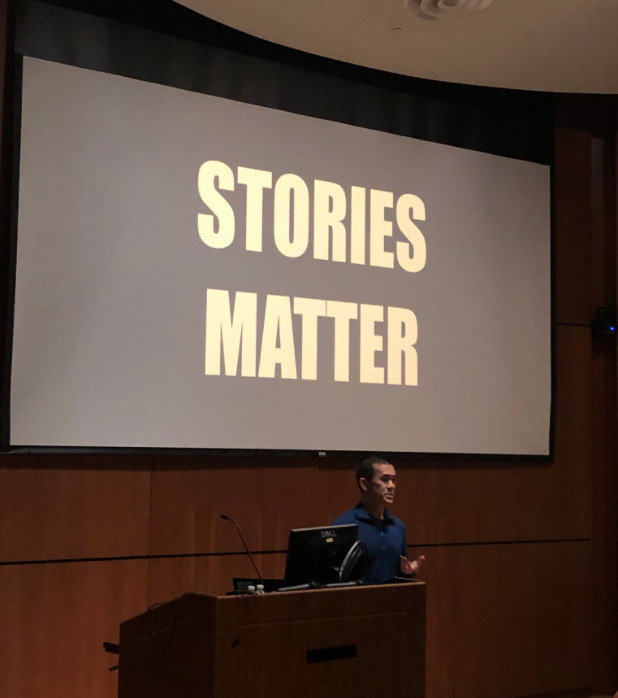

Whether communicating about the complex world of science or using art to illustrate life in America, the “story” is what matters.

The connection between two vastly different worlds struck me a few weeks ago as award-winning science journalist Ed Yong stood before a University at Albany audience. As he shared with listeners his approach to selecting topics and then writing articles about 21st century science, the slide he projected behind him spoke volumes: “Stories Matter.” In a world bursting at the seams with scientific data and research results, The Atlantic magazine writer argued, any journalist attempting to gain eyeballs as he/she explains a scientific topic needs to appeal to the basic curiosity of the masses through simple and effective story telling.

The author should endeavor, he added, to “Get people to care about things they wouldn’t otherwise care about.”

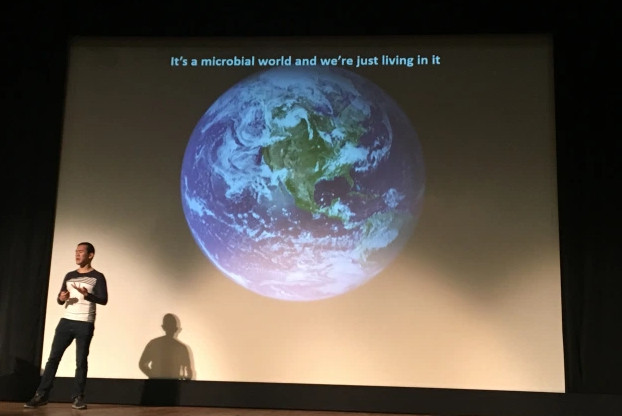

Science journalist Ed Yong discusses his craft at the University at Albany (courtesy of The RNA Institute at UAlbany)

A month earlier, I visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass. During a day spent gazing at the famed illustrator’s 323 Saturday Evening Post cover paintings and other original works of art that help tell the story of 20th century American life, I listened to Rockwell himself explain his approach to painting. In a video recorded shortly before his death in 1978, he said: “I love to tell stories in pictures. The story is the first thing and the last thing.” I blogged about it.

As a lifelong student of the creative process—from music to writing to art—I had within the span of four weeks had some of my long-held beliefs about that process upheld by two immensely different but talented individuals. Embed a simple story into whatever you’re crafting and, whatever your message is, people will be drawn to it.

Yong’s Book: We. Are. Microbes

Well, maybe about half of us, according to Yong, who appeared at UAlbany Feb. 19 as part of the New York State Writers Institute spring 2019 series. It’s a well-known fact that the human body is made up of millions of living cells, composing structures ranging from our brains to our bones. But that’s only half the story.

In his book “I Contain Multitudes – The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life,” Yong tells us the rest of the story. Beyond those living, pulsing cells lives a collection of trillions of tiny microbes that make up the rest of our bodies. These tiny bacteria, viruses and other organisms chugged along for millennia, out of sight and without recognition for the role they play in our lives. They finally achieved some recognition, Yong told his Albany audience, when Dutch microscope maker Anton Van Leeuwenhoek discovered their presence in the 1600s. A few centuries later, scientists including Louis Pasteur discovered their role in causing illnesses. This 19th-century development of the “germ theory,” however, gave microbes a bad name because they were associated with making us sick.

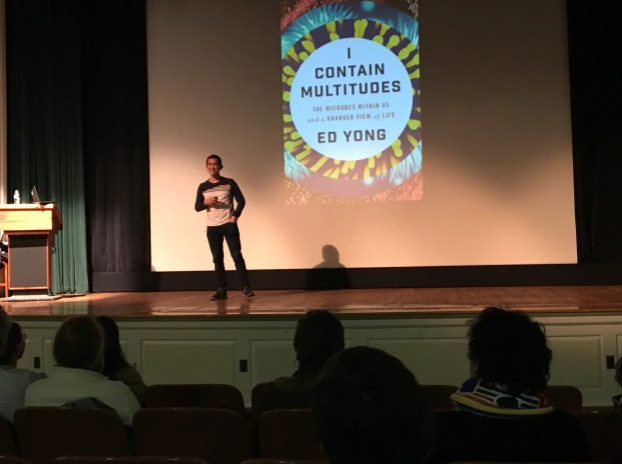

Yong discusses his book at UAlbany

Later, 20th century scientists delved deeper into the microbial world and found that microbes are constantly everywhere in our bodies, and they in fact perform useful functions that help us thrive. Over 400 species of microbes live in the human gut, for example, and aid processes like digestion. They work in sync with our cells, and we should be thankful for them.

Yong’s regular stream of articles contain similar revelations. Readers of his recently learned: Why do zebras have stripes? (follow the flies…), giraffes are close to extinction, sharks can live to 400, we’re the only animals with chins, and one of my personal favorites..how wasps use viruses to genetically engineer caterpillars.

Yong stressed that the scientific and science writing community should hold each other accountable. On the day he appeared in Albany, for example, he published a piece to help clarify a wave of science headlines and social media posts predicting impending doom for the insect population across the world. He argued that while there was some validity to the claims, “it was complicated” and they were based on very limited research.

“And if insects do die out within a century that will mean the planet has become inhospitable to all life,” he concluded.

Focusing on the “how” and Leonardo

Despite Yong’s explanations of his science writing approach at UAlbany’s D’Ambra Auditorium, students, staffers, faculty and others continued to press him to further describe his process. Finally, he answered with:

“I’m almost always led by curiosity—if something makes me go ‘huh,’ I can also convey that sense to a reader.”

Yong’s process is not that far from one aspect of the Leonardo da Vinci described in Walter Issaacson’s biography of the 15-century polymath responsible for paintings like the Mona Lisa and the early scientific foundations behind manned flight. As he drew near the end of the story of da Vinci’s life, Isaacson wrote a section called, “Learning from Leonardo.” The first heading in this segment is titled: “Be curious, relentlessly curious.”

Isaacson wrote further, “…his distinguishing and most inspiring trait was his intense curiosity. He wanted to know what causes people to yawn, how they walk over ice in Flanders (northern Belgium), methods for squaring a circle, what makes the aortic valve close, how light is processed in the eye, and what that means for the perspective in a painting.”

That’s not a bad trait to emulate, and it’s writers like Yong and artists like Rockwell who help us stay curious about the world around us.

Blog author (left) with Yong after his talk at UAlbany