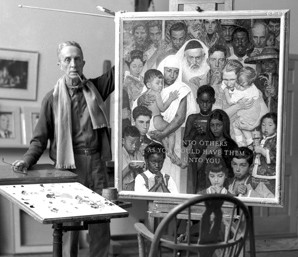

Before he passed away in 1978, famed illustrator Norman Rockwell offered the “secret” behind how he crafted his amazing paintings: “I love to tell stories in pictures,” he explains in a biographical video at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass. He adds that what he was trying to do wasn’t “fine art.” His legions of fans would probably disagree.

“The story is the first thing and the last thing,” he concludes.

A visitor to the wonderful museum dedicated to Rockwell’s life and work doesn’t really need to hear those words. Each of the paintings and drawings displayed at the museum in the Berkshire Mountains depicts a story told via raised eyebrows, dramatic facial expressions, body posture, minutely portrayed details, and myriad other cues that lead viewers to where the New -York-City-born illustrator wanted them to go. From an anxious young couple applying for a marriage license with a time-pressed public official to African-American children meeting their new white neighbors for the first time, the visitor can unravel a story that might take hundreds or thousands of words to explain. Rockwell was that good.

Since the museum moved from its original, cramped location in downtown Stockbridge to its expansive, more rural location a few miles away in 1993, it has opened the eyes of over 100,000 visitors annually from here and abroad. The story of 20th century America is told there through the eyes and paint brush of the lanky artist. Stockbridge was a natural location for the museum since the artist and his family lived there from 1953 until his death, Before that, Rockwell lived in nearby Arlington, Vermont.

The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass. (Photo credit: Norman Rockwell Museum)

Today, the museum regularly displays about 1,000 Rockwell illustrations, and houses over 100,000 items—including letters, photographs, fan mail, and business documents— in its archives. Perhaps the most popular collection on display is the 323 covers Rockwell painted for the Saturday Evening Post. Nearby on the property sits Rockwell’s actual painting studio, but it’s only open in warmer months.

Many of Rockwell’s more significant works are displayed in large rooms, each painted in different color themes, which seem to bring out specific features of each painting. If they take the time, visitors can stand relatively close to some of the illustrator’s works and—depending on the angle of their head and light from the ceiling—see evidence of the actual brush strokes. On the day I visited in January 2019, I spent some 20 minutes examining hardly visible, small ridges of oil paint in a painting Rockwell did for a raisin ad. It was a magnificent piece of work.

An example of one of the rooms in the museum, with a blue color theme

While Rockwell did some commercial work to help clients sell products, most of his work for magazine covers and other projects reflected his meticulous desire to portray real life scenes that tell a story. As a fan of the creative process ranging from music to books to art, I was amazed by the weeks, months and often years Rockwell invested in light/color studies, model selection, and other research before he put brush to canvas. Most people who work at the museum readily explain that Rockwell was rarely satisfied with his finished projects. He would often throw away a painting he had worked on for months and start all over.

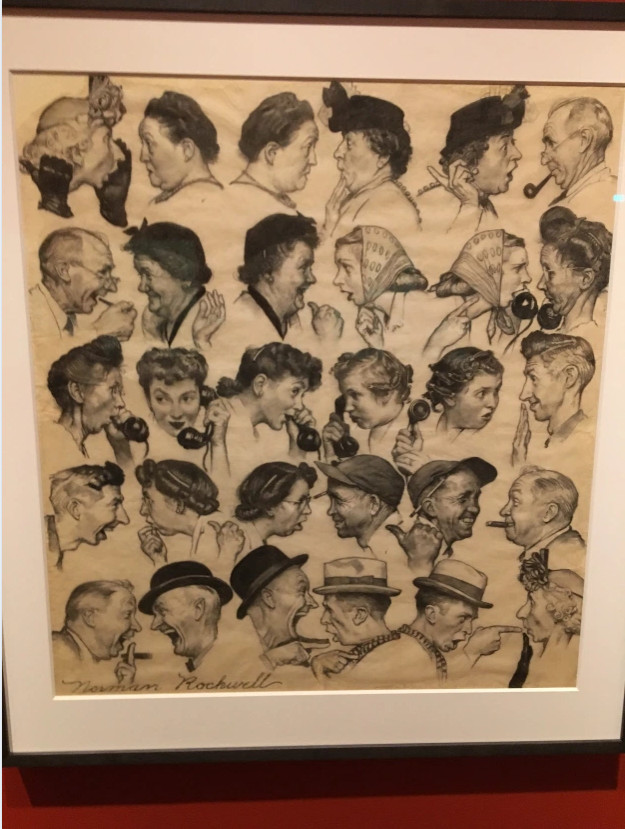

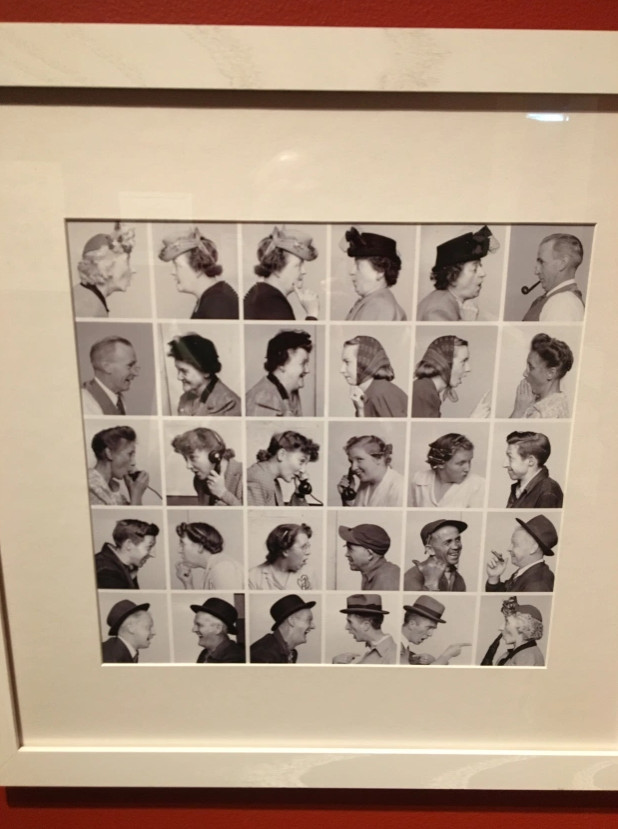

One example is also one of my favorites: “The Gossip.” In the 1948 painting, Rockwell depicts the faces of 15 people in five horizontal rows, often in hilarious poses as they pass along a juicy tidbit of gossip. The exchange of information continues until it finally reaches the subject of the gossip near the end. The last verbal exchange involves the gossip target confronting the lady who started the nasty trail. Since Rockwell gave his paintings a lot of thought well beyond the visual components, he worried that any model he used to portray the object of gossip might be offended. So he used himself as the target. His wife at the time, Mary, also appears. The woman who served as the model for the gossip originator was so upset, according to museum guide Judy, that when she saw the final product, she didn’t speak to Rockwell for eight months.

The story of this amusing illustration also reveals some of the process Rockwell used to achieve his goal. Adjacent to the finished painting, the museum displays a preliminary charcoal drawing and photograph of the models used by Rockwell.

The final version of “The Gossip” painting

A preliminary charcoal drawing Rockwell drew as he worked on “The Gossip”

Another step in Rockwell’s process: a photo montage of the models used for “The Gossip”

In addition to depicting the simple life around him, Rockwell often drew inspiration from major events of the day. He was so inspired by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s famous 1941 speech involving the “Four Freedoms” that Rockwell spent two years painting four masterpieces that bring those four freedoms to life: Freedom of Speech, Freedom From Want, Freedom of Worship, and Freedom From Fear. They can be viewed here.

The four pieces were so popular they were used in efforts around to country to sell War Bonds during World War II. Today, they continue to serve as iconic yet simple reminders of the values at the core of American life. Curious about connections between Rockwell and FDR during the process of painting, I asked museum Curator of Education Thomas Daly if the two had communicated or if FDR had given Rockwell direction. The answer, Daly said after he gave a presentation on the topic to me and other visitors, was probably not! Rockwell simply latched onto the idea from the speech and ran with it. “To the best of our knowledge, FDR and Rockwell only met once,” Daly said.

***

The Rockwell Museum is located at 9 Glendale Road in Stockbridge, Mass. It’s open daily from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m. and an hour longer during the warmer months. Visitors planning the trip should check the website for special presentations, events, and displays: https://www.nrm.org/. Admission is $20 for adults, $18 for veterans, and $17 for seniors 65 and over. There’s no charge for visitors 18 and under, and college students pay $10. Those who sign up and pay for membership receive free admission and other benefits.