By Mark Marchand

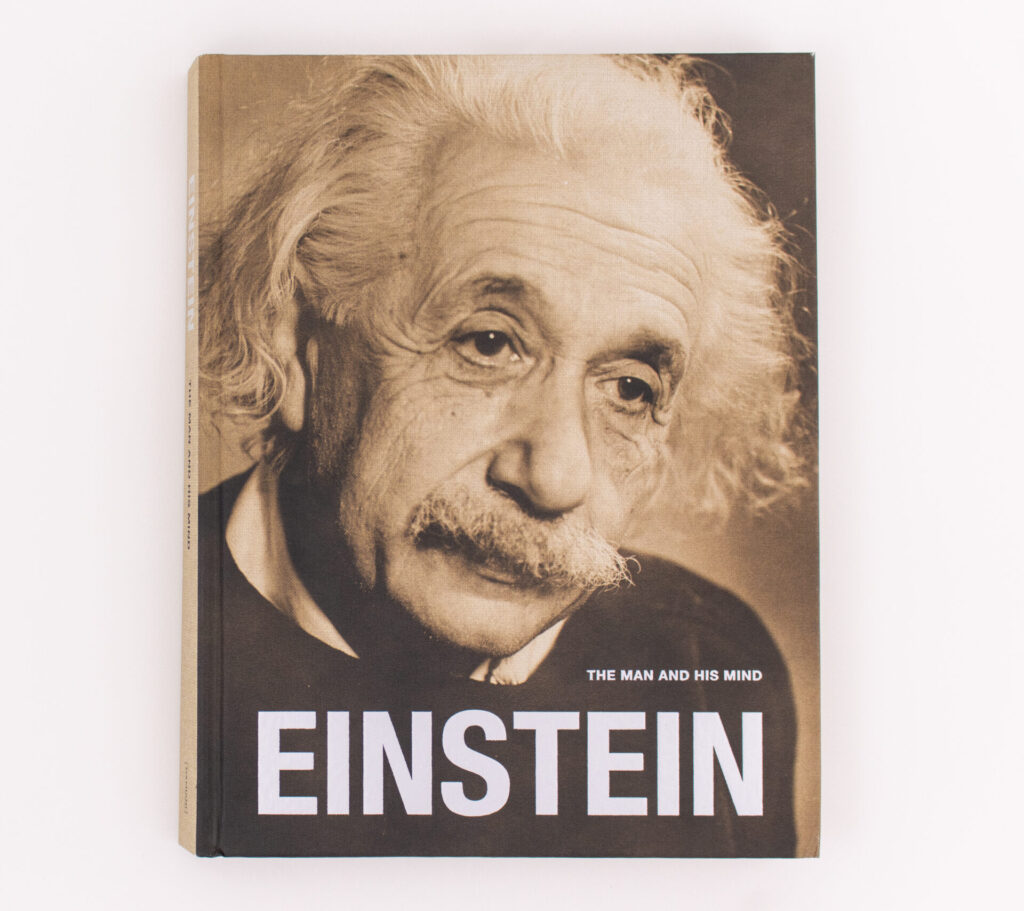

If you stare long enough into his eyes in the many photographs of the man, you might begin to see faint images of atoms splitting … light waves being bent by the sun’s gravity … equations rolling by … a man descending in an elevator … or even musical notes dancing across a staff. This man is Albert Einstein, who peers at us from a new collection of photographs taken over a lifetime during which his “thought experiments” and other work shook the foundations of physics and other sciences.

The authors and others behind development of “Einstein, The Man and His Mind” have published what might just be the most definitive look at the German-born theoretical physicist who forever changed and broadened our understanding of how our world works. Over 50 well-known and rare photographs of the wild-haired, pipe-smoking scientist allow readers of the new book to plumb the depths of those eyes and other physical features. This visual timeline stretches from his early days nattily attired in suits and formal wear while studying and working in Europe to decades later, when he eschewed formal wear for sweaters and his beloved leather jacket while working and walking near Princeton University.

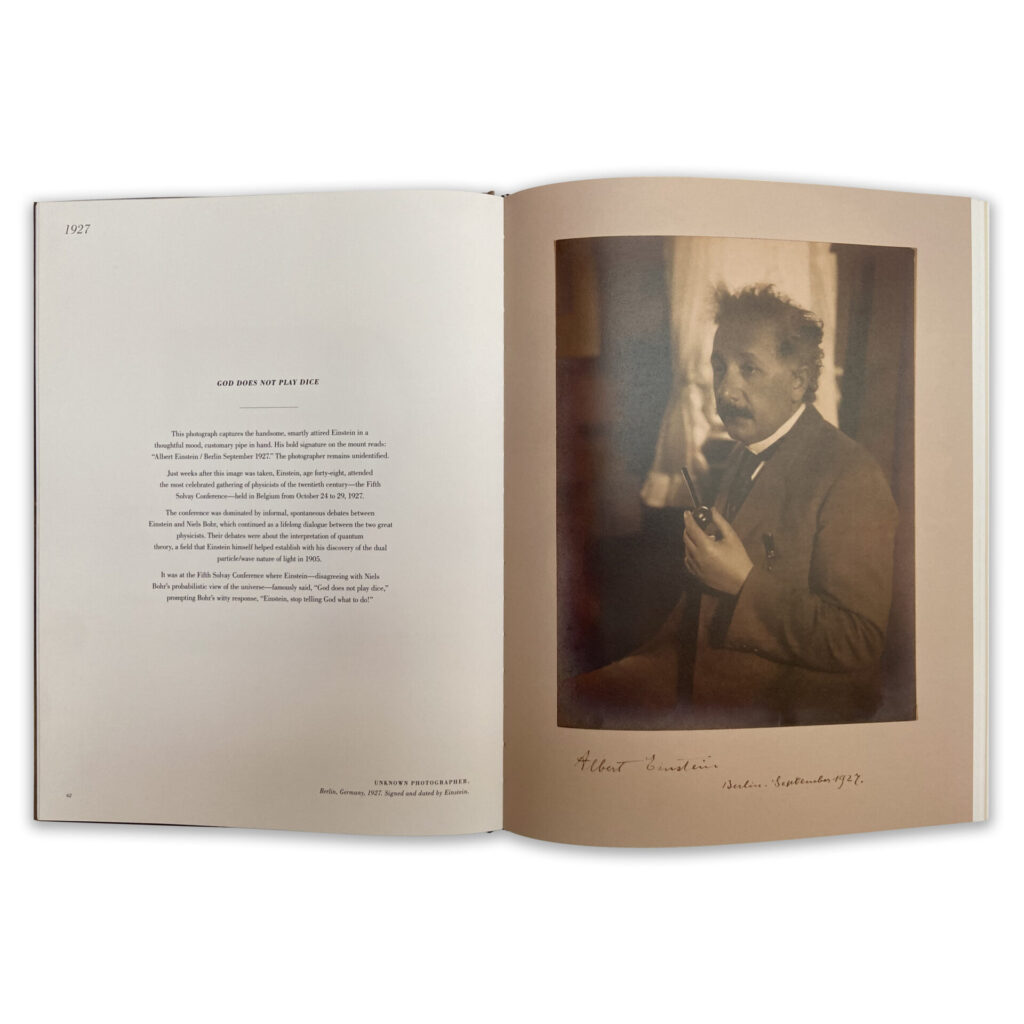

Photographs scattered across the 210-page, coffee-table-sized hardcover reveal a man of character, a man of feeling and care, and perhaps a man demonstrating a bit of impishness—all while retaining the overall air of seriousness one might expect from such a pioneering scientist. It’s easy to understand how his image and reputation forever established in our minds what scientists should look like. As knowledge of his work and pictures of him spread across the globe during the 20th century, depictions of scientists in movies, cartoons, and drawings borrowed from his unkempt hair, thick moustache, and the smoking pipe dangling from his mouth, with a hand on the other end. Even today, an actor playing the part of an absent-minded Einstein helps hawk smartphones in a TV commercial.

The man at work

The book’s many rare photographs include a series of seven taken while Einstein worked in his home at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton, New Jersey. They are my favorites. Russian-American photographer Roman Vishniac arrived for a visit that day in 1942 and hoped to take a formal portrait of Einstein. Instead, according to Vishniac, Einstein deferred sitting for the portrait because “an idea had suddenly come to him, and the room was filled with the movement of the great man’s thoughts.” Einstein stood up and began staring at and re-working formulas on a blackboard, holding his pipe. Vishniac quietly photographed the man as he worked, generating perhaps one of the most revealing series of photographs of the scientist. Wearing a dark, ribbed sweater Einstein went about his work at the blackboard and at his desk. Einstein later remarked that one of the photos was his favorite portrait of himself.

Vishniac, the authors say, in 1980 wrote of the impromptu session, “The originality of Portfolio ‘Einstein’ consists of its special character. It is made not to get images, but the feeling that you are present during the creativity by the Great Man.”

The beginning, and near the end

I have two more favorites in this new collection. They form a set of bookends on his life. First is a photo I’d seen before. In this earliest known snapshot, ca. 1896, a dark-haired very young Einstein stares into the lens during a session the authors suggest was related to Einstein’s graduation from the cantonal school of Aaru, Switzerland. He donned a formal jacket and vest for the occasion, and sported a necktie in a thick knot hanging from a white collared shirt. He later recalled it was one of the happiest years of his life, during which his independent thinking emerged.

According to the book, Einstein recalled: “In Aarau I made my first rather childish experiments in thinking that had a direct bearing on the Special Theory (of relativity) …. If a person could run after a light wave with the same speed as light, you would have a wave arrangement which could be completely independent of time. Of course, such a thing is impossible.”

My second cherished picture in the new collection was taken near the end of Einstein’s life, in 1954. He died from a ruptured aneurism a year later, at the age of 76. In the photo he signed for the photographer, Einstein is seated in his Princeton home, holding a pipe while stuffing tobacco into it with the thumb of his right hand. Both hands rest on his lap. He’s wearing a dark V-neck sweater that hangs loosely on his aging frame. He appears tired, almost sad, and his moustache and wild, still-thick hair are totally white. Wrinkles and creases spread across his face while the skin covering his cheeks droops toward the moustache. The years appear to have weighed heavily on him. Still, if one stares at the photo long enough, a slight smile is detected. And his eyes, perhaps a little more closed than usual, maintain that piercing, curious gaze for which is famous. The photographer, Frederick Plaut, later remarked that he was in such awe of his subject he could scarcely focus his camera. When Einstein asked Plaut if he was going to sell copies of the photo, the photographer said no. Einstein seemed disappointed and, according to the authors, said, “Not sell them? If I had known that I would never have let you take them.”

The story that accompanies the photos

While the photographs, copies of Einstein’s letters, and re-prints of the covers and some of the text from his papers published in science journals are reason alone to spend hours with this book, the authors didn’t cheat us when it came to the accompanying text. Using a crisp narrative style, they describe the setting and background for each photo and include commentary from some of the photographers.

Even better, they reached deep into the archives of Einstein’s writings and lectures for some well-known and not-so-well-known quotes.

On the facing page before Vishniac’s 1942 collection of photos, for example, appears a revealing 1952 comment from the scientist: “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.” Another gem that appears in the book emerged from his post-World War II regret over signing a 1939 letter, along with physicist Leo Szilard, alerting then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the potential to create “extremely powerful bombs of a new type.” The letter helped move FDR to create the Manhattan Project, leading to the first atomic bomb. In a 1947 interview with Newsweek magazine, the book authors report, Einstein said, “Had I known the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing.”

A final, touching quote in the book was uttered by the scientist from a Princeton hospital bed, shortly before he passed in April 1955. He had just refused surgery for a leaking aneurism that had caused stomach pain for years. “I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.”

His life, beyond science

Readers of the book will not only learn more about the Nobel Prize-winning Einstein but a recurring theme resonates throughout: He was an ardent supporter of humanitarian causes, pacifism, and his Jewish faith. He supported some German Jews as they escaped the horrors of Naziism (after he himself fled Germany for England and then the U.S. in 1933) and sought other opportunities to make a societal impact, extending well beyond his scientific work and achievements.

This new, vibrant telling of the Einstein story was the brainchild of two authors: Michael DiRuggierio, owner of the Manhattan Rare Book Company, and Gary S. Berger, M.D., a retired reproductive surgeon who spent three decades collecting original Einstein publications, manuscripts, letters, and photographs. Many of the photographic selections in the book are housed in Berger’s private collection in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Retired theoretical physicist Hanoch Gutfreund, academic director of Albert Einstein Archives at Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a renowned Einstein scholar, contributed the book’s forward and other input.

And in the true spirit of their admiration of the man and his achievements, all proceeds from sales of the 212-page, 10 x 13-inch hardcover (published by Damiani of Italy) will be donated to the Einstein Archives at Hebrew University. Two private U.S. Foundations provided support for the project: The Sterling Foundation and The Antonia & Vladimer Kulaev Heritage Fund, Inc.

To read more about the book or to purchase it, visit this link.