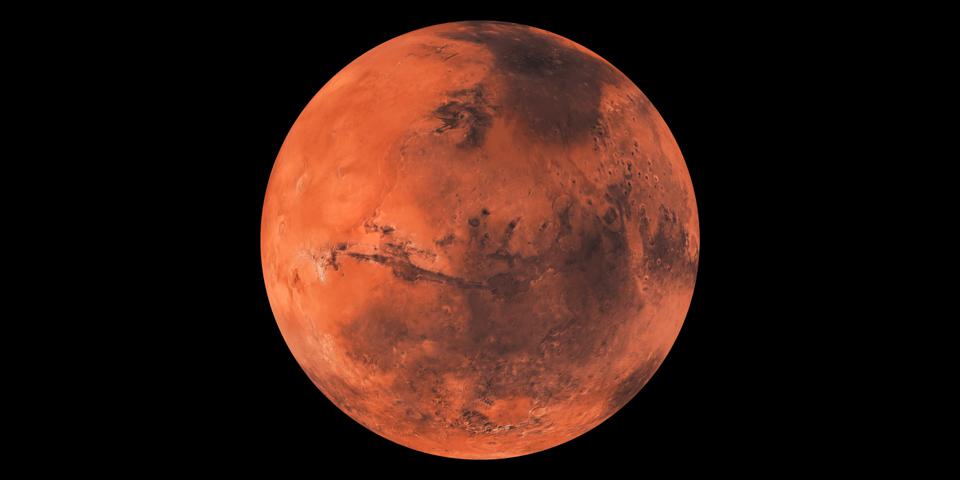

This is a good week for space exploration buffs like me. There’s a literal traffic jam in orbit and on the surface of planet Mars as three new arrivals complete their 300-million-mile sojourns from Earth at the same time, celestially speaking. Two of the new arrivals will remain in orbit, bringing to 14 the total number of unmanned spacecraft circling the planet. Six are active and collecting scientific data. The other eight, sent beginning in 1971, quietly circle, their sources of power or ability to operate long since expired.

The third new arrival—which is generating much of the news these days—skipped orbit and headed straight to Mars’ surface in a fiery descent so scary NASA scientists have coined the procedure “the seven minutes of terror.” It was a huge success, but more on that in a bit.

***

The red-tinged planet named for the Roman god of war has always been our favorite space exploration target—and the focus of myriad science fiction stories, books, and movies since the 19th century. Mars Invasion. Attack from Mars. The Martian Chronicles. War of the Worlds. You get it.

As Mars welcomes its largest round of orbiting and surface visitors, the total Earth missions dispatched to our nearby planetary neighbor just hit 49. Since the dawn of the Space Age in 1960, nine nations or multination agencies have dispatched robotic missions there. It’s a hard job, though. More than half those missions failed, including an expensive 1999 NASA attempt when an orbiter was lost due to a simple conversion error between metric and English measurement units.

Most of those failures occurred during earlier missions. We’re getting better. Since the summer of 2003 we’ve only lost one of 24.

The latest and busiest round of robotic exploration of the Red Planet started Feb. 9 with the arrival of United Arab Emirates’ “Hope” probe. The UAE’s first such mission, Hope will circle the planet to study Martian weather. A day later, China’s “Tianwen-1” probe successfully entered Mars orbit. This mission is a little more complicated. Tianwen-1 will orbit the planet for a few months, searching for a suitable landing spot for a small rover the Chinese National Space Agency hopes to send to the surface in May.

This busy period reached a crescendo Feb. 18 when NASA’s “Perseverance” rover reached Mars and headed straight to its risky landing at Jezero Crater. The site was picked because it appears to be a spot where ancient rivers and streams dumped waterflow into what might have been a lake whose water evaporated eons ago. There’s a good chance the suspected riverbed and dry lake contain vast deposits of sediment that could reveal clues to past or present existence of water and/or microbial life.

Like the successful 2011 NASA “Curiosity” rover mission (still active today), the car-sized Perseverance packed with scientific apparatus plunged into Mars’ wispy atmosphere at 12,500 miles per hour. The craft deployed a large parachute but, due to an atmosphere less than one one-hundredth as dense as Earth’s, Perseverance needed much more drag to slow down for a safe landing. About 7,000 feet above the surface, a rocket-powered descent platform deployed and slowed Perseverance down enough for a safe landing. As the apparatus neared the surface, a series of cables slowly lowered Perseverance to the ground. The process was even more challenging because mission controllers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California didn’t know immediately how successful the pre-programmed maneuver was. It takes 11 minutes for radio signals from Mars’ present position to reach Earth. The scene was joyous, though, when the team received landing confirmation. Controllers wearing their pandemic-required masks whooped it up and shared fist bumps. The first photos from the rusty-colored, rocky surface arrived within minutes.

There’s a lot more to Perseverance’s planned mission of scientific study, photo-taking, and other experiments. This rover will be the first to collect soil samples and store them in a group of sealed cylinders until two future missions retrieve them for return to Earth. The elaborate process will feature a future robotic rover that rolls up to Perseverance, grabs the samples with a robotic arm, and launches them into orbit. A third future spacecraft, orbiting Mars, will attempt to capture those samples and haul them back to scientists here. I’m breathless just thinking about it.

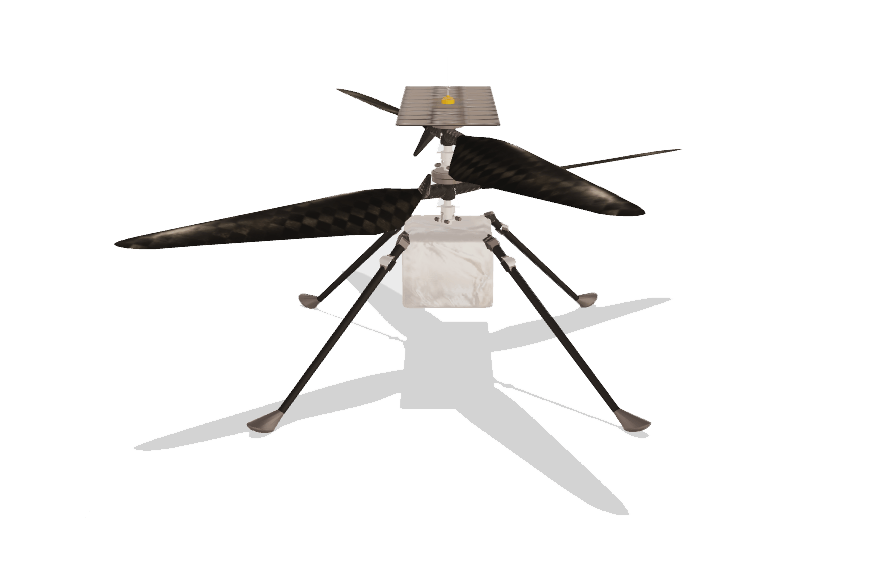

Another first for Perseverance will harken back to the Wright Brothers’ achievements over a century ago. Our new mobile explorer on six wheels has brought with it a remote-controlled helicopter, with blades designed specifically to fly in Mars’ thin atmosphere. Scientists hope the demonstration project will pave the way for future airborne exploration of the Red Planet. The small solar-powered chopper, called “Ingenuity,” carries two cameras, a computer, and navigation sensors.

To find out more about the mission and to follow it “live,” head to NASA’s mission website. Now for a bit of folklore.

***

This busy season for Mars exploration fueled a blizzard of news coverage and discussion. One of my favorite summaries of the event appeared in the Planetary Society’s latest podcast. Host Mat Kaplan entertained listeners with tales contained in author Marc Hartzman’s new book, The Big Book of Mars: From Ancient Egypt to The Martian, A Deep-Space Dive Into Our Obsession With The Red Planet. I haven’t had time to read it yet, but if Hartzman’s stories during the podcast are any indication the book should be on any space exploration fan’s list.

Here’s a sampling of lore Hartzman shared in the podcast:

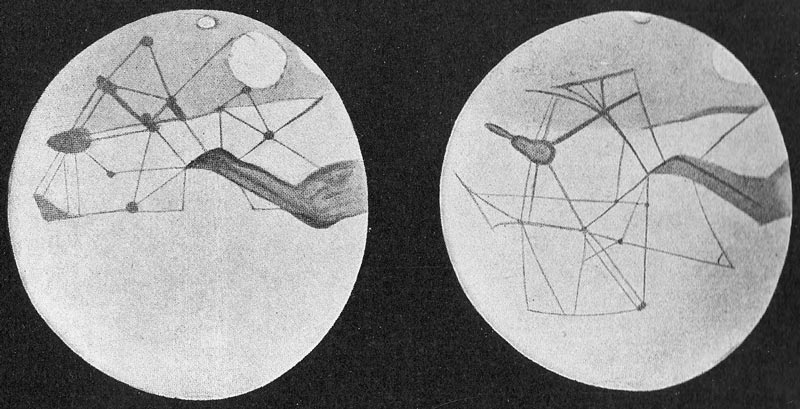

Canals? Much of the early writing and photography on Mars focused on “canals” that were supposedly built by an advanced society. Many theorized the canals were constructed to transport water from the wetter poles to the drier, desert-like plains near the equator. It turns out this was more of a language issue.

Using a low-powered telescope in 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaperelli first described the straight lines he thought he was seeing on Mars. He used the Italian word canali. American astronomer Percival Lowell and others added their thinking. They theorized that the only explanation for the lines could be irrigation canals built by intelligent beings. As better telescopes were developed, it turned out that the lines didn’t really exist. They were an optical illusion. The situation was made more confusing by use of the word canali. Lowell and English speakers translated it directly to “canals,” which implied they were manmade. It’s also true that the Italian word can mean channel, duct, or gully. These words refer to surface features that could occur naturally. Better observations and some science continued to clear up the confusion. For example, early 20th century scientists explained that the air pressure on Mars was simply too low to allow the existence of surface water. Still … if only those canals were real.

Mars calling? As development of wireless communication advanced in the late 19th century, many scientists and entrepreneurs tried to contact Mars, according to Hartzman. It was sort of a wacky pursuit that even distinguished scientists like radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi pursued. During his research and experimentation in 1920, he started receiving strange radio signals comprised of wavelengths 100,000 meters long. Nothing like that existed on Earth at the time. Marconi theorized the signals were coming from Mars. He kept studying the signals to determine their extraterrestrial source. A few years later he was brought back to Earth, in a sense. He found out the unusual wavelengths were coming from a secret radio experiment at General Electric in Schenectady, New York. As Hartzman says, that was probably quite a come down for Marconi.

They’re here: No discussion of Mars folklore is complete without a reference to Orson Welles’ 1938 live radio broadcast reenactment of H.G. Wells book “War of the Worlds.” (Am I the only one who sees the links between those last names?) Many listeners thought it was real and panicked. This was even though the broadcast began with an announcement of the production being part of the Mercury Theater on the Air storytelling series. Some tuned in after that introduction. One of the best features of the show, according to Hartzman, was how Welles started it. He began with band music, so it sounded like a routine show. He then broke into the broadcast with a shocking news bulletin, announcing the detection of a series of explosions on Mars. The music resumed, followed by more urgent bulletins about a strange object falling in Grovers Mill, New Jersey. Hartzman explains that war was brewing in Europe and people were pre-disposed to hear real, breaking news alerts. It was mystery radio at its best. If you have about five hours, you can listen to it here.

***

There’s a lot more material on the topic, but I’ll stop here … for now. I intend to follow Perseverance’s progress in the coming months and years. The photos that are already starting to be sent back here are astounding. The Scientific American magazine gives us a peek at what to expect for the first 100 days.

I’m excited to see what we learn. As a species, we are meant to explore … so explore we will.

Interesting read! Nice to finally know what was up with the “canals” after all these years.