Most people consider bridges as structures built for convenience and safety. They are so ubiquitous that we take them for granted, scooting over them in cars, trucks, and trains without much thought. The only time we pay attention to them is when one of them fails spectacularly, like the I-35 bridge in Minneapolis 13 years ago. Fourteen people were killed and 145 injured in that catastrophe. In a similar disaster, a major bridge in Genoa, Italy, crumbled to the ground in 2018, killing 43. The public reaction to bridge tragedies is similar to the shock that follows airline crashes, a rarity in one of the safest means of travel today. We react in horror to both, but soon we find ourselves back on bridges or jetting to places thousands of miles away. Bridge collapses and airline accidents temporarily ding the trust we place in both. But because we need them so much, we forgive … and forget.

I am no different than most when it comes to bridges. But the way they are built, their history, and what they look like fascinates me. This enchantment began when I first crossed the George Washington Bridge connecting New York City to New Jersey during a family trip in the mid-1960s. Later on that same trip I saw the Pulaski Skyway Bridge arching up from the swampy lands of eastern New Jersey. I didn’t realize it until I got home weeks later that I had taken 50 photos of both bridges. Family members who were on the trip were disappointed I didn’t take one picture of them. I was hooked on bridges.

One of my favorites has always been the majestic Brooklyn Bridge. Construction on that still heavily used span connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan began in 1869—just four years after the Civil War ended. I was finally able to walk every inch of this bridge in 2014. I wrote about that magical experience here in my blog.

The second reason I’ve always loved bridges is more allegorical. To me, bridges are a metaphor for constructing a means—physical or virtual—to connect to something: ideas … the future … the past … even linking one part of a song to another. I recall with some humor how I came up with the phrase “Connections to Tomorrow” in 1986 when I was searching for a theme to describe new technology being deployed in Boston by my employer, a Verizon predecessor company. Each time I looked at that phrase after we printed it on brochures and giveaways, I thought, “I should have used ‘bridges’ instead of connections.”

***

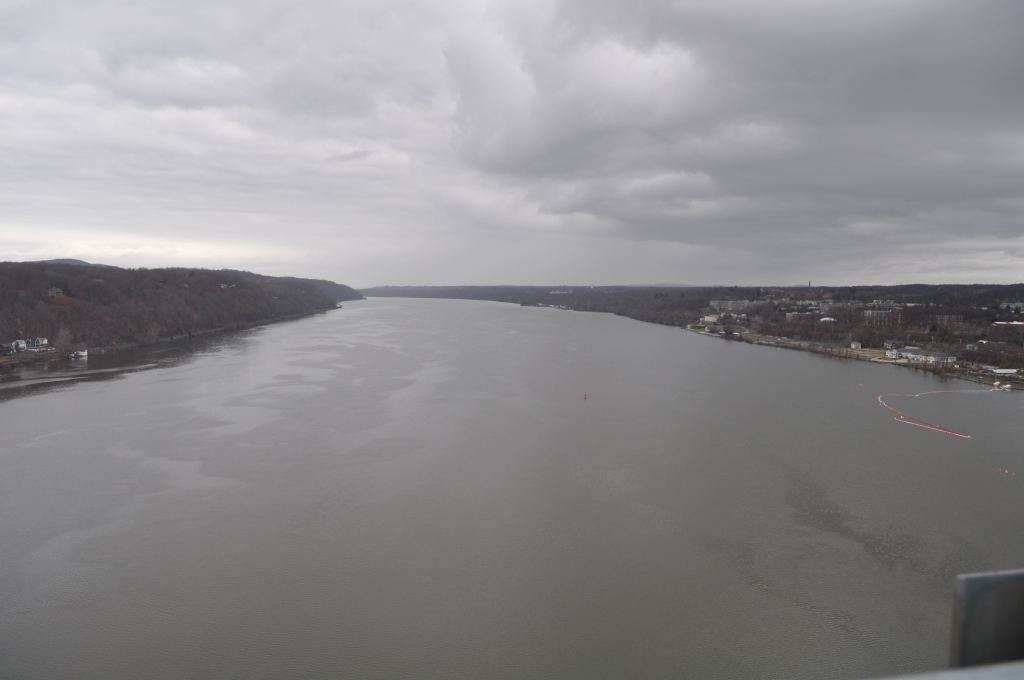

Last month, I crossed another bridge experience off my list. About 90 minutes south of where I live in Upstate New York sits the Walkway Over the Hudson. This combination park/pedestrian footpath spans the Hudson River, soaring to over 200-feet above the waterway. The 1.2-mile crossing links Highland on the west bank to Poughkeepsie to the east. The structure started life as a railroad bridge in 1889. Freight and passenger trains rumbled over the span for decades, until a fire destroyed the tracks and closed the bridge in 1974. It remained shut until an ambitious group of organizers decided to turn it into a pedestrian walkway years later. Their efforts paid off when the superb footpath opened in 2009, welcomed by widespread positive reviews and thousands of walkers.

Since then, the walkway has grown in popularity and became part of the Hudson Valley Rail Trail network: three connected trails extending for 18 miles over paved pathways. On the day I visited, I quickly learned the pandemic had not slowed the flow of walkers and bicyclists searching for new acreage to explore.

***

I drive to Highland on an unusually warm Friday late in November. I’m delighted to find that most precious of commodities when visiting outdoor attractions in rural areas: a building containing clean restrooms. Even better, it’s powered by solar panels. After a quick stop there I begin my eastbound walk along a paved pathway leading to the bridge. The slowly rising path features several signs and maps that help visitors find their way. Stopping to look at one diagram I learn that I can cross the Hudson, meander through downtown Poughkeepsie, and return to my car on the west side of the Hudson by walking across a second bridge. The bustling Franklin Delano Roosevelt Mid-Hudson Bridge is a mile south and carries thousands of cars and trucks across the river. That steel suspension bridge features a pedestrian path just inches from the traffic. I’m thrilled. I get to walk two bridges. I resume my stroll, brushing by other walkers, runners, and bicyclists. Many hikers are accompanied by their dogs.

Since we all need to remember we’re in the midst of a pandemic, urgent warning signs abound. They tell us masks are mandatory and suggest schemes for remaining socially distant. On both sides of the walkway are steel, chest-high barriers with vertical beams. In some places there are higher chain link fences. I surmise they are intended to discourage visitors from throwing debris to a roadway below. More somber are the signs offering help via phone for someone who might be considering suicide.

As I near the halfway point of the walkway, where it arches to its highest point above the river, I’m rewarded with stunning views of the Hudson north and south, along with rising hills and greenery. I stop for a few selfies with my phone and snap pictures of the landscape with my single-lens reflex camera. The skies on this day are mostly gray, with low clouds. The sun breaks out infrequently. I catch short bursts of conversation from other walkers, some of whom speak in different languages. As I resume walking after my photo session, I see a group of students from a nearby college. They’re wearing sweatshirts and hats with their school logo. One is video chatting with her mother on a smart phone. “Mom, this is so amazing … I’ve never walked across a bridge. Let me show you …” The young female student then pans the setting with her phone.

I reach the point where the walkway starts to slope downward toward Poughkeepsie. I stop and sit on a bench to take it all in. No one would have ever been able to witness this unique view if the river walkway hadn’t been created. Driving a car across a bridge does not allow the type of scenic absorption I seek on my walks. I’m thankful. I get up and head to Poughkeepsie.

Once I “land” on the east termination point of the walkway I study the map again. I’m confused by the route it suggests through the densely populated city, and I give up after a few minutes. Google Maps is easily accessible on my phone, I think, in case I get lost. I turn right at the end of the path and descend another slope onto the city streets.

Within minutes I’m lost. None of the street names match those listed on the sign back at the bridge. I pull my phone out and launch Google Maps. I wait for the screen to populate … and I wait … and I wait. Nothing happens. I give up after five minutes and decide to navigate by myself, using a general sense of where I think the Hudson River sits. Once I find my way to the river, I know all I need do is turn left and walk to the Mid-Hudson motor vehicle span. I try this and I find myself even more lost. I’m by myself in a congested older city and I have no idea where I am. The only thing I have going for me is daylight. I continue walking. I’m hemmed in, though, by rows and rows of two-story houses and apartment buildings. I can’t see where I’m headed.

Still hopelessly lost a few minutes later I come upon my savior in the form of that omnipresent, friendly, geographically smart public servant: a mail man. He’s loading envelopes and small packages into a temporary holding container just off the main street. I place my mask back on because he’s wearing his. I explain that I’m lost and trying to find the trail to the bridge south of where we stand. He has apparently heard the same question before. He quickly says, “I think they want you on Verrazano Avenue, turn left, and then you follow that to the train station and riverbank area.” He explains how to find Verrazano from where we stand. I thank him profusely and continue. I find the street and arrive at the Metro North/Amtrak train station a few minutes later. From there I know it’s easy to get to my second bridge of the day. I find a small park along the river to sit and rest for a few minutes. The flow of water from right to left is mesmerizing

A few blocks south of the train station, I ascend a series of steps to reach the Mid-Hudson Bridge. The noise from two-way traffic is deafening. I also find myself enclosed in a narrow steel and concrete walkway. I experience the same claustrophobic feeling I did years earlier when I entered the walkway along the Manhattan Bridge. Today I have rising girders and heavy traffic on my left and a steel railing separating me from the long drop to the river on my right. There is barely enough room for two-way pedestrian traffic. But that isn’t a problem on this day. I’m alone as I walk west.

Somewhere near the halfway point I discover an unusual gem. The designers engineered a sort of music station where visitors can press a button and listen to melodies that could only be made by sounds from the bridge. Composer Joseph Bertolozzi produced a series of instrumental pieces based on rivets being pounded into metal and other noises, like “playing drums” on the walkway girders and guardrails. The feature is simply called “Bridge Music.” I listen to a few samples. I did not expect such unusual evidence of the arts on a dreary, utilitarian structure. I’m impressed.

At the end of the bridge, I clamber down more steps to reach a path that takes me back to my beginning point. I discover a food truck selling kettle corn and soda. I also need to rest before the long drive home. I buy a bag of popcorn and a Coke and sit for a while looking at the much larger crowd now assembling at the walkway entrance. Everyone is masked, except for those appearing to be part of an immediate family. Most visitors sit more than 6 feet apart. Dogs strain at their leashes. Children restlessly pull on their parents’ arms. I detect a vague difference from similar scenes I have witnessed in the past. I suddenly realize it’s the volume level of conversation. The louder, more distinct clips of dialogue are muffled by masks. Oh yes, I think, it’s that pandemic thing again. I finish my snack and head to the restroom for one last visit. Some three hours after I arrive, I’m headed home.

It’s winter now and we’ve just been belted by a major snowstorm. I’m using the downtime to start looking for the next bridge to walk. A friend recently told me the Tappan Zee replacement bridge, the Mario M. Cuomo span, has a walkway. It’s over three miles long … but I’m game for the round trip.