By Mark Marchand

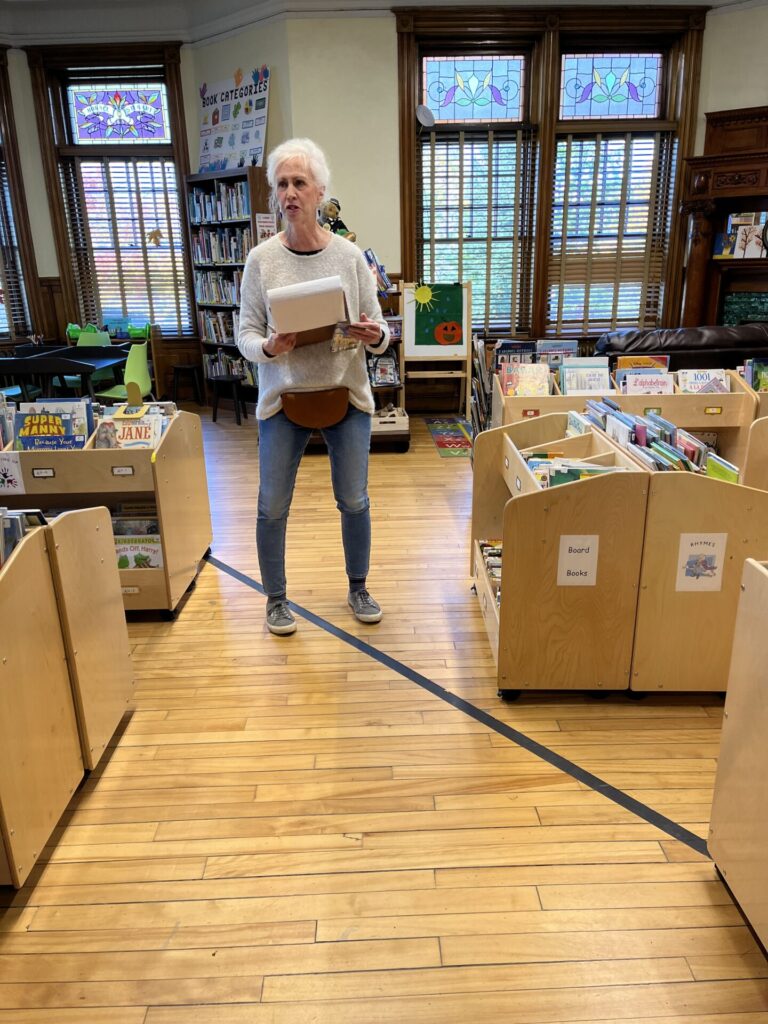

As she speaks to visitors on a bright fall morning recently, volunteer Lynne Coutts could be one of many other tour guides in the thousands of libraries serving readers throughout North America. Dressed in a white sweater, jeans, and sneakers, the slender, white-haired Coutts engages her followers on this October weekday with a blend of history, facts, and unique anecdotes about a facility she is so obviously thrilled to talk about. There’s so much to explain, she carries a clipboard with facts so she doesn’t miss anything.

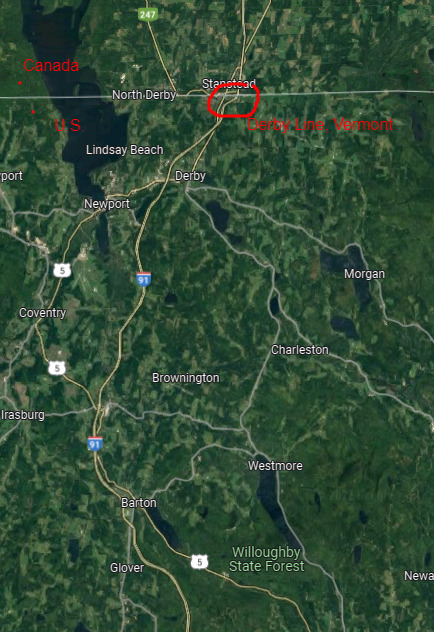

It would be easy to mistake Coutts and her presentation for a normal day at any library. But then there’s that dark-brown strip on the hardwood floor passing between Coutts’ left and right feet. A closer look reveals the books on her left are written in French. Those on her right are in English. There are other clues that lead the uninformed to better understand this setting. Outside the windows behind her is a fence that restricts visitors walking by. Every few minutes a uniformed customs guard appears. Unlike in almost any other library in the U.S., Canada, and perhaps the rest of the world, Coutts is straddling an international border that carves right through the nearly 120-year-old Haskell Free Library and Opera House. The well-preserved, three-story, tan/gray building sits directly atop the U.S.-Canada border in the tiny hamlet of Derby Line, Vermont. Almost any time you wander from one location to another inside you’re crossing the border.

To those who think such an unusual location for a library was a site-planner’s mistake, she assures her guests it wasn’t. “This was no error,” she explains. “The designers and builders decided to put it right on the border.” She’s quick to add that such a location was allowed during construction in the early 1900s, but by 1920 regulations and new international laws would have prevented it from being built on this location.

The reason for the international frontier location, she continues, was to foster an appreciation for and spread of arts, culture, and literature among residents of the border communities of Derby Line and Stanstead and Rock Island in the mostly French-speaking Quebec Province in Canada. All three shared a strong sense of community despite the border in 1900, and still do today.

The “opera house”

The border-squatting aspect of Haskell is not it’s only unusual feature. As its full name implies, a stunning architectural marvel of a performing arts center occupies the entire second floor of the building. Coutts is quick to point out the 360-seat facility has never hosted an opera. “It was just the custom at the time to call a theater hosting live events an opera house.”

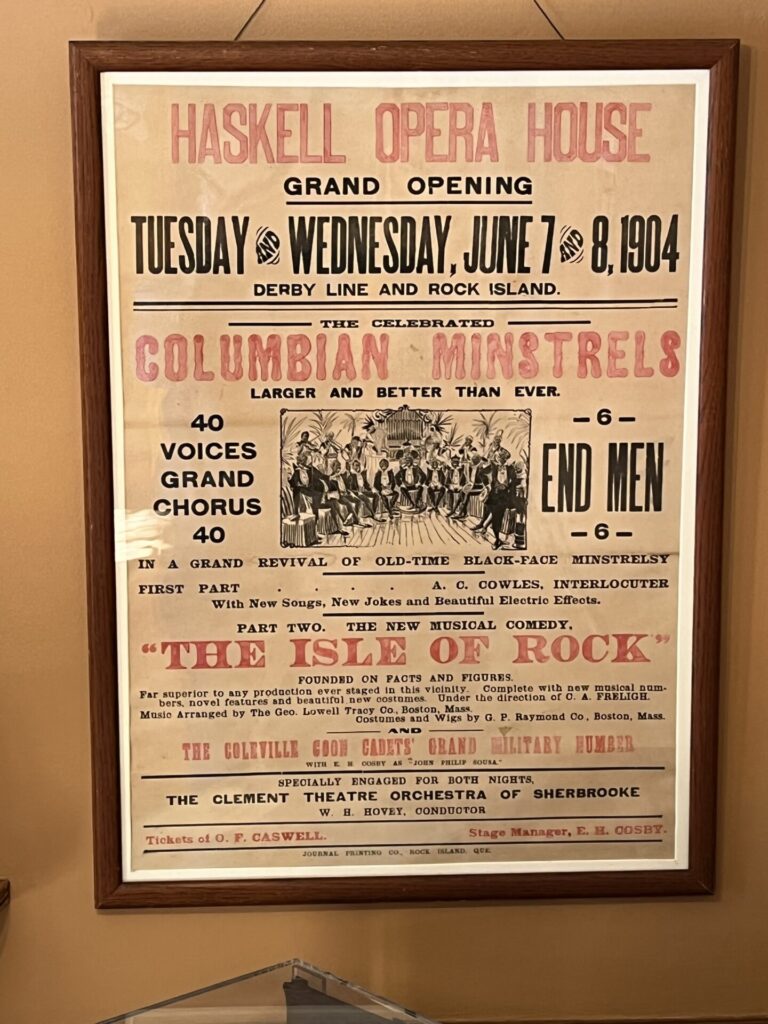

When the opera house opened on June 7, 1904—the downstairs library followed a year later— the first show booked was a minstrel group that touted “black-face minstrelsy” as one of its features. Yes, it’s the same type of blackface acts that draw widespread condemnation in these more racially sensitive times and are generally banned. Still, Coutts says as she points to the original poster advertising the show hanging in the hallway leading to the theater entrance, it’s a stark reminder of a vastly different time.

“We’ve sometimes drawn criticism for having this poster here, but it’s part of our history. We can’t deny it.”

The appearance of Haskell’s performing center could rival that of many well-known theaters throughout the continent. The wooden chairs of the first floor curve toward an elevated stage adorned with curtains, lighting, and other sophisticated equipment usually associated with live, professional shows. Upstairs is a balcony—or the “cheap seats,” as Coutts says—that forms a full half-circle from one end of the stage to the other. As she leads her visitors through the balcony, she points out a few unusual features. One recessed corner, for example, is used today to control lighting and sound from a control panel. It didn’t always serve that purpose.

“After the hall was opened in 1904 this corner served as a ‘corset relaxation room,’” she explains. “Workers hung a curtain across the opening so the ladies could come back here during a break or intermission and well, sort of unsnap, untie, and breathe a little before tightening everything back up and returning to their seats.” Her visitors chuckle. I can tell the young girl with her parents on this day is not sure what a corset is.

And then there’s that Beatles rumor from 1972. Folklore has it, Coutts says as she completes her tour of the opera house, that the four Beatles were looking for a place to meet in person but were dealing with legal and immigration issues. John Lennon was living in New York City at the time, but he didn’t have his green card yet. He worried, according to various versions of the story, that if he left the U.S., he wouldn’t be able to get back in. At the same time, some of the other Beatles were worried about returning to the U.S. because of drug-related matters. Since the Haskell sat on the border, the Beatles reasoned, Lennon could sit in the U.S. side of the building while Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr sat a few feet away on the Canadian side. One can only imagine how that conversation might have gone.

The story goes on to say the meeting was called off when local police decided they couldn’t handle the crowds and chaos that would surely accompany any meeting of the Fab Four two years after they broke up. While different versions of the story can be found on the internet, there is little hard evidence to support the tale.

“Many people still talk about it and wonder if it was true, but no one is really sure,” Coutts says when she finishes the story, throwing her hands up. “Still, it’s part of the many stories that add to our long history, so we mention it to visitors.”

As today’s visitors exit the theater with her, Coutts stops to point out that most of the audience for performances sit in the U.S. The performers are in Canada. The same small border marker found on the first floor runs along the floor leading toward the stage.

Where it all began

According to the Haskell website and official history, the library and opera house were conceived and funded by Derby Line resident and Canadian native Martha Stewart Haskell and her son, Colonel Horace Haskell. They dedicated the effort to Martha’s late husband Carlos, a prominent local merchant. Since Martha was born in Canada and Carlos was from America, it made sense for the family to erect something that would encourage cross-border culture exchange. Construction began in 1901 and was completed three years later when the opera house opened while construction continued on the downstairs library.

Mrs. Haskell chose Rock Island architect James Ball to design the building. He partnered with Boston designer Gilbert Smith to achieve the final Queen Anne Georgian and classic revival styles used in final construction. Smith used some elements of the old Boston Opera House in his design.

Today, according to Coutts, little has changed with the structure and internal design of the building. The same curved tin ceiling moldings, large oak door frames, fireplaces, wood theater seats, and other physical features remain—and have been meticulously maintained. There are a few signs of the 21st century: An elevator in the back of the building helps visitors avoid the narrow set of stairs leading to the theater, and computer screens appear in a downstairs reading room. The library itself serves French- and English-speaking readers and borrowers. In addition to over 20,000 books, the library loans DVDs, audio books, and provides WIFI access.

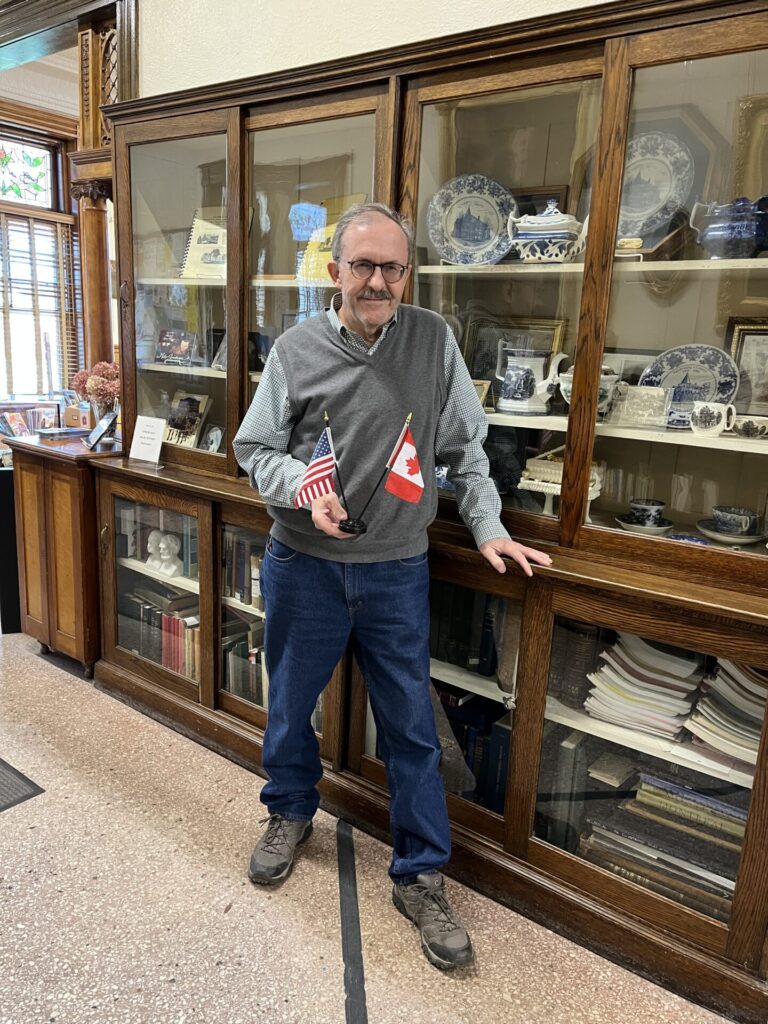

Over the years the Haskell team has learned to deal with peculiar aspects of operating a facility that sits in two countries.

“We need, for example, to deal with two sets of contractors, two sets of plumbers, two sets of electricians, two different phone lines, and other complications because the requirements are different in both countries,” Coutts laments. “But we’re used to it.”

Visitors coming from two countries also presents a challenge. The front entrance is located on Caswell Avenue in Derby Line in the U.S. That presents no issues for American visitors. Canadian guests must first park in in back of the library and follow a prescribed walking route to the front door in the U.S. They typically don’t need documentation but must return to their cars along the same route. The area is patrolled by Canadian and U.S. customs officials who have the right to ask visitors from Canada to produce identification or ask them questions. Just down the road is a formal customs checkpoint for visitors driving to Canada. Nearby is a U.S. Customs gate where all returning citizens and Canadian visitors must check in. Haskell visitors typically see a steady stream of customs officials from both countries roaming the area.

Today at Haskell

These days the building, its staff, its volunteers, and its borrowers/visitors are like a slowly awakening organization after a long sleep. The pandemic hit it hard. The facility remained closed for over two years.

“It’s refreshing to not only be hosting visitors and tours again, but we’re also planning the first shows since we temporarily closed in 2020,” says Melanie Aube, interim librarian. “Everyone’s anxious to get going again.” Aube herself is a great example of the international character of Haskell. She commutes to work each day from her home in in Quebec.

The library is open Tuesdays through Saturdays, from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m., except for a 4 p.m. closing on Saturday.

The area

Derby Line and the nearby larger town of Derby are quaint, friendly communities that offer four-season reasons to visit. In addition to fall leaf-peeping and winter sports (famous Jay Peak ski resort is only 30 miles east) and widespread availability of maple syrup stores and production facilities, the area surrounding Haskell is rich with warm-weather tourism opportunities. The southern banks of the nearby massive Lake Memphremagog, for example, offer lakeside dining and water activities ranging from boating to fishing. Like Haskell, this lake straddles the international border and stretches well into Canada.

A little farther down the road from Derby sits the larger city of Newport, the government center for Orleans County. This community features many restaurants, pubs, stores, and hotels.

While Haskell and Derby Line sit at the most northern point in Vermont, it’s a relatively easy drive from the rest of New England and the Northeast. Interstate 91 plops drivers right into downtown Derby Line.

(Click here to visit the Haskell website. True to the nature of the institution, you can read it in English or French. Click on “Francais” on the upper right to see the French version.)