Chapter 1

By Mark Marchand

This series of posts about my road trip last summer originally appeared on my Medium blog page. I’m placing it here for readers of my website. It’s a long read but I guarantee that it’s entertaining and somewhat enlightening!

(Editor’s note: Last summer I set out from my home in upstate NY to search for an America readjusting to life as the COVID wildfire slowed down. Just as I was about to depart on a celebratory, wandering road trip through seven states the Delta variant began sweeping our country. I went anyway. Below is the complete four-part series on my sojourn. Like many of my road trips across America, it was a fun excursion— but the worsening news about COVID was an overhang on my mood, haunting me each mile along the way.)

July 27, 2021:

My glasses fog up as I climb from my air-conditioned car into swampy heat at a northern Indiana highway rest stop. While my tank is half full, I’m not sure where the next rest stops are on Interstate 90, the highway guiding me home after a wandering 2,000-mile drive through seven states. Topping off my gas tank has become an obsession.

I extract a credit card from my wallet and set to work. Within seconds I get an “approved” message. I insert the nozzle into the opening for my gas tank, squeeze the trigger, and stare at the screen tracking gallons and price.

Nothing happens. I stop squeezing the nozzle and restart. Nothing. The screen on the pump reverts to the welcome screen for new customers. Has my credit card been charged without any fuel being dispensed? Such are the doubts of a tired, weepy driver who’s been on the road weaving through truck convoys, heavy traffic, summer construction lane closures, and serpentine routes through Milwaukee and Chicago since early that morning. I sigh loudly and try the process again. Same result.

I start looking around, wondering if others are having the same problem. Everyone’s busy pumping. My roving eyes reach the lower right side of my pump. I spot the end of a disconnected black hose on the ground. Employing my amateur detective skills, I trace the hose. It leads to my nozzle. I laugh out loud, relieved. It occurs to me someone must have driven away with the nozzle still stuck in their car, ripping the hose from the pump. And of course, that driver politely placed the disconnected nozzle back into the pump slot.

A few seconds later it hits me. I realize the situation is a metaphor for the angst … the frustration … the sadness … the pure anger that has permeated my thoughts on what was supposed to be a fun road trip. The reason for my dour feelings? Refusal of millions to take the safe, proven vaccines that could eventually steer us clear of this COVID mess. The same people and descendants of people who are alive today because of polio, measles, and other vaccines are subscribing to political ideology under which they shouldn’t be forced to vaccinate — prolonging the national agony begun over 18 months earlier. We have the vaccines. They’re free. But a stubborn minority won’t take them.

The disconnected hose on the ground becomes my broken vaccine delivery system. The nozzle is the hypodermic syringe standing ready to plunge into arms. And the fuel system reservoir above me is my ample supply of Moderna, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines. The persistent refusal of many to take the jab, as they say in England, is my disconnected fuel hose that won’t fill my tank.

It’s apparent I’ve been thinking about this too long when a few other motorists start beeping at me. They notice I’m standing there doing nothing. Backing up to a nearby pump I try the process again. Success! Perspiring heavily, I drive away to collect my thoughts. I park and write down a few notes about the experience before returning to eastbound I-90. It’s back to poking along behind 18-wheelers trying to pass other 18-wheelers uphill. But the chance encounter with the broken pump remains on my mind far into the next state on my way home.

***

My sojourn to this spot adjacent to nonstop, roaring traffic on I-90 in Howe, Indiana, began five days earlier in upstate New York. My physical and emotional state has swung wildly; from the pure joy of the open road to my struggle to escape worsening pandemic news.

Day 1: July 23, 2021

I grip the wheel tightly as I pull out of my driveway to leave home in Saratoga County, New York, on a steamy summer day. For the second time in seven years, I’m off on a long solo drive, temporarily leaving behind my wife and comfortable home north of Albany. My goal is different from my no-itinerary 2,400-mile jaunt down U.S. Route 1 in 2014. I started that road trip at one end of the highway in northern Maine and drove until I hit Key West two weeks later. Along the way I stopped to talk to people and soak in the sights and sounds of a highway opened in 1926. I spent the next three years thinking about it, curating over 700 photos and other records and writing a book.

My goal is different in the summer of 2021. I want to drive west instead of south but, more important, I want to see how my country is doing after the devastating pandemic. I had originally postponed my drive in 2020 because of virus and state travel restrictions. I resumed planning as the spread waned in June 2021. But as I assembled final schedules in July, COVID-19 crept back along a southern stretch of the U.S. from Florida to Texas — primarily due to low vaccine acceptance and the more infectious, deadly Delta variant. We even saw the numbers tick up to a lesser extent in the more heavily vaccinated Northeast and parts of the Midwest. I remained steadfast in my plans. I’m vaccinated, I wear a mask most of the time, and I would be driving through seven states with low infection numbers. I would soon learn that there’s no escape from the bad news about the virus, through social media and other digital means.

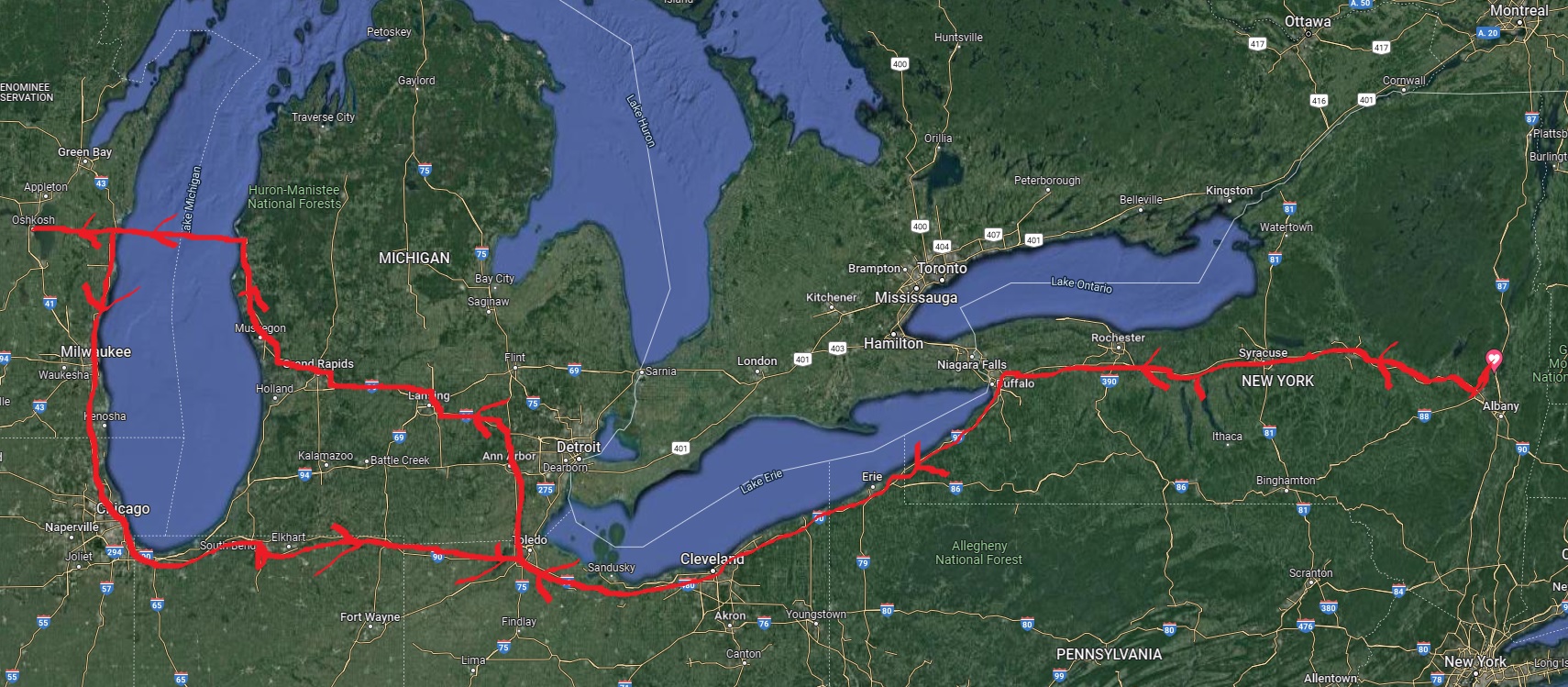

Unlike my Route 1 drive which had no itinerary, this time I worked in three specific stops: a ballgame in Cleveland, a Great Lake car ferry ride, and the world’s largest annual air show in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Otherwise, I left things loose. I discovered one remaining stumbling block before leaving: The U.S.-Canada border remained closed due to COVID. I had planned a shortcut through the province of Ontario to Michigan, but I was out of luck. I sketched a longer route to the south, remaining in the U.S. Armed with my car’s GPS system and a Rand McNally Road Atlas, I set off.

***

Just outside Saratoga I opt to put off entering I-90, my intended primary route. I take local roads through nearby Schenectady and then Route 5 into the city of Amsterdam, where I’ll pick up the interstate. Along Route 5 west of Schenectady, the Mohawk River/Erie Canal burbles quietly to my left. Its silty brown color is the result of heavy recent rains. I think about a book I recently read. Blue Highways author William Least Heat Moon set out in 1995 on an ambitious trip: navigating from the East Coast to the West Coast in a small boat — motoring exclusively on twisting, sometimes treacherous rivers. He started with the Hudson River in New York City and finished at the Pacific Ocean in Oregon. “River Horse: A Voyage Across America” is the story of his challenges on the trip. After leaving the Hudson River he journeyed the stretch of the Mohawk/Erie Canal I’m passing now. I give his memory a metaphorical wave before finding my way through Amsterdam to the interstate.

I-90 in upstate New York is notable for what you don’t see. Unlike mostly local Route 1, which steered me through intricate cityscapes like New York and Washington, D.C., the New York State Thruway conceals the cities of Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and other major burgs. I’m not complaining. The rolling, green hills along the road and parallel Mohawk River create a scenic vista that convinces the lonely driver he or she is in remote, untouched wilderness. Staring at this nearly endless procession of small green peaks reminds me of one of the first science fiction stories I read as a high schooler. Robert A. Heinlein in 1947 penned a short story about spacemen traveling the Solar System, much like sailors piloting cargo ships around our globe. At the center of this historic short story is a songwriter who works on interplanetary spaceships. Later blinded in an accident aboard one of those ships, Noisy Rhysling writes one last verse:

“I pray for one last landing on the globe that gave me birth; Let me rest my eyes on the fleecy skies and the cool, green hills of Earth.”

Recalling literary pieces and fragments of stories from famous writers proves to be a constant theme on this drive. It helps distract me from the social media platforms constantly bleating bad news and hyperbolic projections for catastrophic near-term futures. Speeding west at over 70 mph, I think of how that magical, romantic Heinlein story helped spark a lifelong passion not only for reading science fiction but also reading for pure enjoyment.

I make a few unsuccessful stops at Thruway rest stops to buy lunch. Many of the normal fast-food counters are closed. The few that are open sell mostly pizza, a nonstarter for a guy with lactose intolerance. My hunger grows. Very few rest stop visitors wear masks. One stop takes place in Chittenango, the birthplace of L. Frank Baum, the author who gifted the world with the book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the basis for the famous movie that enthralled legions of fans since it’s release in 1939. I’ve spent hours trying to decipher meaning from various parts of the movie, but in the end I’m always in awe of Baum’s ability to craft such a magical, mysterious, work of fantasy. I always found it interesting that he grew up in such a small, remote part of upstate New York — which hardly provides inspiration for the Emerald City.

***

Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo slip by without showing themselves. Traffic grows heavier and often slows to a crawl south of Buffalo as I-90 angles southwest toward Erie, Pennsylvania. I weave through fleets of large RVs. Americans are on the move again, and they’re taking their bathrooms, kitchens, and bedrooms with them.

West of Erie, already 400 miles from home and thinking about my first overnight stop in Cleveland, I develop a cramp in my right foot, which I realize has been in the same position for hours. I normally use cruise control on interstates, but traffic is thick and I give up because I’d be constantly activating and deactivating the device. I take my foot off the gas pedal for a few seconds at a time and glide while I stretch the toes and rotate my ankle. The cramp subsides.

***

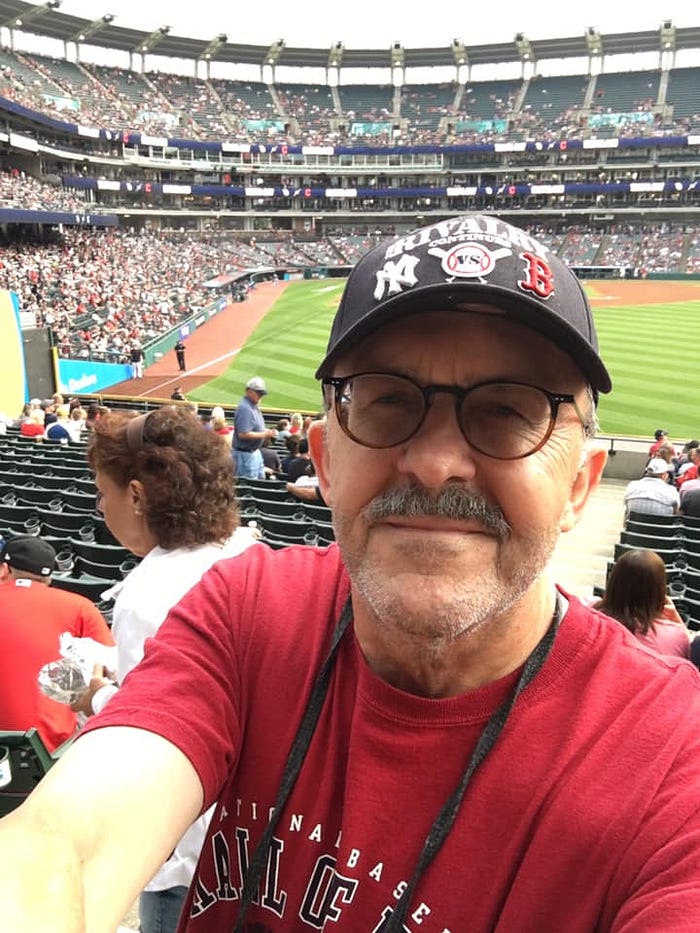

If there were such a thing as a steady chromometer in my life it would be baseball. The game has always been part of the tapestry of my life, stretching back to my early days as a Boston Red Sox fan in the 1960s to more recently when I hopscotched around the country in a small airplane to see games. I planned my first overnight stay in downtown Cleveland, a short walk from Progressive Field where the Cleveland Indians (now The Guardians) play.

I arrive 20 minutes before the first pitch. I’m delighted with myself, technologically, because I managed to load my ticket onto my smartphone. Twenty feet into the stadium I discover a $2 beer stand. It’s a special pregame offering on Friday nights. I line up several times and text pictures to friends, boasting about my discovery.

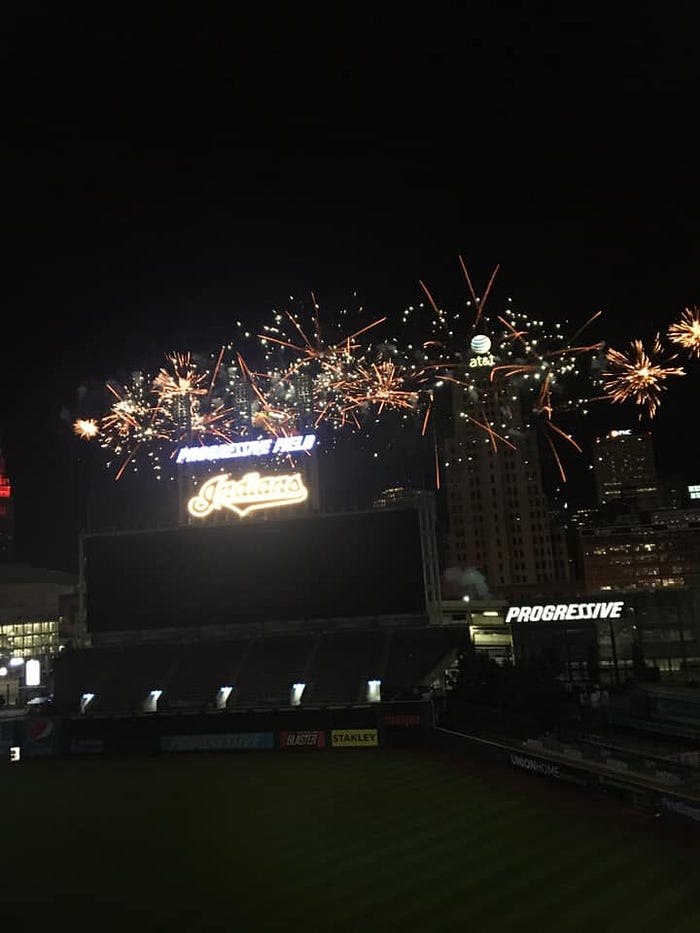

I wander around beneath the stands and then settle into my outfield seat before the first pitch against the visiting Tampa Bay Rays. There are few fans sitting close to me. My COVID-meter goes down. It’s my first ballgame in almost two years. I enjoy the experience on this beautiful night even though I don’t follow either team. The Rays end up winning 10–5. During the seventh inning, the announcer asks fans to remain after the game for fireworks. That experience turns out to be the best part of the night. In the ninth inning, I position myself for the best vantage point to see the show. I climb some stairs and settle into a seat in the upper deck near the right field foul pole.

Ten minutes after the last pitch the show starts. The dark skies north of the stadium explode in brilliant red, blue, yellow, green, and orange streaks — accompanied by an eardrum-rattling soundtrack of 1980s music. The heavy-metal guitar music and screamed lyrics ricochet off nearby buildings. I am moved to tears and sing along with the songs I recognize. I forget about COVID over the next 20 minutes. I haven’t been this happy in months. Head pitched skyward, I capture some of it on my smartphone to post later. My cheeks hurt because I’m smiling for more than a few minutes at a time. Has it been that long since I wore a sustained grin?

With a few more awe-inspiring bursts, the show thunders to a conclusion around 10:45. Others around me get up to leave, but I wait in the hopes that maybe they’ll shoot up one more burst … an Easter egg of sorts for those still hanging around? No such luck. Around 11 I get up and join the masses exiting the facility. Outside, I meander through large groups on the way back to my Holiday Inn Express. Sleep doesn’t come easily. I stay up and make a few notes on the day before closing my eyes around 1 a.m.

Next week in Chapter Two: Northwest into Michigan and abandoning the steering wheel to cross Lake Michigan.

Chapter 2

Tunnel vision

My trip west of Albany last July would differ in one more significant way from my 2,400-mile U.S. Route 1 drive in 2014: I would abandon local roads and take speedier interstate highways. My plan was to stick to I-90 all the way from Albany to western Ohio, where I would veer northwest to Michigan via smaller interstates, state highways, and local roads.

I knew it would be different, but I wasn’t prepared for how different. The two- or three-lane interstates would steer me away from major cities and traffic-clogged local roads, allowing me to hit speeds of 65 mph and faster. About 100 miles west of Albany, I slowly developed a better understanding of this mode of travel, which came into full bloom west of Erie, Pennsylvania.

My little black car and I are trapped in a “tunnel” of sorts on I-90. I’m walled in by heavy traffic and foreboding guard rails that won’t let me off the highway until exit ramps. I feel like a red blood cell trapped in a blood vessel, eventually cascading through a network of smaller blood vessels and, then capillaries — which in this case are local roads. The interstate “tube” in which I’m trapped allows me to see little else but trees, cars, trash along the breakdown lanes, and trucks. Lots of trucks. I expected it but I’m disappointed to see little of the country through which I’m passing.

On previous road trips I was fond of spotting something interesting and turning around to investigate. Some of those stops provided the best parts of my trips. On this trip I feel disconnected from the world.

I try to avoid aggressive driving, but fail. When I’m behind a slow truck in the far-left lane I move to one of the right lanes to pass. At times I’m accelerating to 85 and squeezing myself back into a narrow opening in the center lane. Each time I do, this I swear I won’t do it again. But I break that promise the next time I’m behind a truck doing 60.

Boredom prevails. I dance around the satellite radio dial in search of music that will distract me. I sing to myself. I recite passages from favorite books. I practice fretting chords on an imaginary guitar. I think about what I’ll do when I reach that day’s destination. And I fight drowsiness.

Approaching Michigan, I decide that future road trips will not include interstates. I’m done. The divorce with Eisenhower’s 1950s dream of a nationwide high-speed road network is final. The experience is too antiseptic.

Day 2: July 24, 2021

I’m awake before dawn in my Cleveland hotel. Visions of last night’s fireworks linger in my mind. Even though I went to bed late, I’m anxious to move on before rush-hour traffic. I pack and head to the lobby, where I check out and scan a few newspaper front pages. COVID dominates the headlines. My mood darkens early in the day.

Leaving the hotel parking lot, I stop for gas before navigating my way back to I-90 west. Within a few miles from Cleveland and its dense suburbs, I’m immersed in a dizzying array of farm fields. Most feature acres of tall corn stalks. I had no idea this much agriculture existed in northern Ohio. The greenery is refreshing. Long, strange-looking metal irrigation structures that crawl over fields appear.

Two hours from Cleveland, I-90 steers me through a congested network of highways around Toledo. It’s here that I plan to turn north but stay west of Detroit as I enter Michigan. I exit onto I-474 before heading northwest on U.S. Route 23. This four-lane roadway is a little like the interstates but much more scenic and connected to the local environment. It reminds me of parts of Route 1.

Approaching Ann Arbor, I start to think about where I’ll stop to rest and eat lunch. I know I’m near the University of Michigan and its famed football stadium, but I press on to East Lansing to explore Michigan State University. It’s more of a halfway point for me today.

At noon I pull off the highway to find Michigan State. It doesn’t take long. This massive campus spreads out over 5,000 acres. I stop for photos and selfies in front of Spartan Stadium, a colossal brick/steel facility. The stillness in the empty parking lots around the field is a stark contrast to the mayhem and joyful chaos that I know exists on fall Saturdays. A few families have parked to take photos like me. A warm wind blows litter around empty lots.

I drive around the campus for 20 more minutes, staring at what seems like an endless collection of dormitories. How will this school, I think to myself, keep its students safe when they return in a month? I exit the campus on the north side, turning left onto Grand River Avenue in search of lunch. I finally spot a small pub. It offers that most precious of commodities in a world wrestling with a pandemic: an outdoor seating area. I park next to Crunchy’s, walk inside, and ask for a seat outdoors. I sit at a table buffered from the nearby traffic and noise by tall potted plants. Server Caitlin asks me for a drink order. “Bloody Mary,” I say, adding that I’ll also have chicken wings.

While I wait for my food and sip my drink, I scribble a few notes about my day in a New York Times branded notebook. Nearby sits a young family, enjoying their meal while struggling to keep two toddlers engaged and eating their food.

Caitlin returns with my food and spots my notebook. “Are you a reporter?” she asks. “No,” I reply. I do write, and it gets published from time to time, I explain, but mostly I blog about life and my exploits on my own website. Still, she seems interested. “What is life working at a pub adjacent to one of the most famous sports campuses in the country?” I ask. The petite young server with a blonde ponytail pushes back a few strands of hair that have fallen in front of her face. She smiles before answering.

“It’s fun and very different depending on what time of day it is,” she says. “During the day we get a lot of families who are visiting, checking out the campus. It’s a far different story at night with the students … or on football days. It’s pretty wild.” I ask her to elaborate about the student clientele.

“Because of our location, most students who are starting an evening pub crawl begin here, and then work their way down the road … so they’re less drunk and less rowdy here. We do enjoy having them here.” We chat about her work and the campus environment for another five minutes. A carwash next door to the pub springs to life every few minutes. The air dryers drown out our conversation, causing us to pause. She chats for a few more minutes before hustling off to serve others. I finish my wings and a second drink, pay my check, and use the restroom before heading back to my car.

***

I leave the hustle and bustle of East Lansing to pick up I-96 west/northwest toward Grand Rapids. This part of Central Michigan is wide open and green with few communities along the interstate. This is certainly not the Michigan that springs to mind when most think of this Great Lakes state. The highway guides me around Grand Rapids, terminating in Muskegon along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. I’m anxious to get away from the busy interstates. I turn off onto U.S. Route 31 north, toward my destination for the day, now a few hours away.

Traffic thins out on Route 31. I keep trying to catch glimpses of Lake Michigan to my left, but the summer vegetation and inland route of the road prevent it. About 10 miles north of Muskegon, amid scarce traffic and more sweeping expanses of green, I experience a feeling similar to “breaking free” situations I had flying airplanes. After the denseness of Cleveland, Toledo, Ann Arbor, East Lansing, Grand Rapids, and Muskegon, I find myself feeling liberated. There are literally no cars on the road with me. A few birds circle lazily above me. I turn my radio off and crack open the windows to revel in the silence and fresh air. I think back to the challenge of flying an airplane on instruments through thick layers of clouds. Those were times that required intense concentration, strict adherence to air traffic control commands, and rapt focus on the instruments. I’d abruptly break free of the clouds and find myself bathed in brilliant sunshine below blue skies, in an almost other-worldly environment. Beneath me was a soft pillow of thick clouds. Around me was profound stillness. I was alone and, it seemed, temporarily cut off from planet Earth. It was unsettling at first, and then I’d become accustomed to it and enjoy the feeling. I dreaded diving back into the clouds to land, upsetting those delicious moments of solitude. It was that feeling that rushed back to me alone in my car in sparsely populated western/northern Michigan.

***

Nearing 5 p.m. I enter Ludington on the Lake Michigan shore. I plan to stay there for the night. I’m exhausted but excited. I’ll catch a few hours of sleep before taking a giant car ferry across the lake to Wisconsin. I’ve been looking forward to the voyage aboard the SS. Badger, which is sure to be a throwback experience on a vessel that first went into service in 1953. It’s the last coal-fired, steam-engine-powered car/passenger ferry in the country. I’m also anxious to get away from the steering wheel.

I find the motel I’ve booked for the night and park. The overall experience at the motel ends up to be terrible. The staff speaks very little English. The room is tiny and smells. The bathroom is cramped. The Wi-Fi doesn’t work. The window of my room is a few feet from the busy main road. Noise from the ineffective window AC unit resembles an airliner on takeoff. The threadbare linens on my bed appear to have been manufactured during the Hoover Administration. The front desk staff tries repeatedly to fix the Wi-Fi, and fails. And horror of horrors: There’s a sign on the motel’s one ice machine warning me not to fill a cooler. The water and soda bottles in my car will have to remain warm for another day.

I resolve to spend as little time in the room as possible, except for sleeping. I drive down to the lake to watch the sunset. Ludington is a beautiful, charming lakeside resort community humming with families on summer vacation. I enjoy the drive around town. COVID doesn’t seem to exist here. I see no one wearing masks.

My final stop is a local brew pub where I buy a draft beer and drink outside. I linger over my drink for a half hour before leaving. I‘m exhausted and decide to skip dinner. Back at the motel I fall into a restless, dreamless sleep around midnight.

Day 3: July 25, 2021

After choking down a muffin and coffee in Ludington, I arrive at the ferry embarkation line 90 minutes before the ship sails west across Lake Michigan at 9 a.m. I’m fourth in line. A staffer greets me, views my ticket, and gives me a small sign with my name on it to place in my windshield. He asks me to leave the car and keys, and stand in line by the ship. Badger workers will drive the car on for me and squeeze it into a tight space to allow for 180 other cars, trucks, RVS, vehicles with trailers, and a variety of other automobiles.

The ferry ride was meant to give me a break from driving. At this point, I had already driven over 800 miles. A short cut on the ferry would allow me to avoid driving west along the bottom of Lake Michigan, through Chicago, and then north in Wisconsin to the farthest place from home on my trip: Oshkosh, aside Lake Winnebago.

It did all that and more. The boat ride, I would soon discover, would be the most enjoyable part of the trip.

The Badger is an impressive sight at first. It’s much bigger than the ferries many travelers are accustomed to, including Cape Cod ships to Martha’s Vineyard/Nantucket or the most venerable of ferries, the Staten Island vessels. Stretching over 410 feet and reaching upward for seven stories, the Badger resembles the utilitarian cargo ships used to ferry goods and soldiers across the Atlantic Ocean during World War II. The metal hull is painted black from the bottom up to the point where the first of two outdoor balconies and walkways appear, along with the reassuring collection of big lifeboats. A wide bridge structure for the captain and crew sits atop everything, stretching from port to starboard and featuring large windows. The Badger is no brightly colored Carnival or Princess cruise ship adorned with flapping pennants, deck-top bars and pools, and multiple levels of windows from which passengers can view the sea. The appearance of the Badger says, “I will get you from point A to point B, with some degree of comfort.”

I explore a few areas once I reach the top of the stairs. My fellow passengers, many of whom seem to know where to go, buzz around looking for a choice seat or perch from which to view the lake or slumber. Some settle onto lounge chairs on an open deck at the front. Even though it’s sunny it’s still a little chilly and breezy for the open front deck. I settle in a large indoor room with tables for four and a cafeteria. Fruit cup and coffee in hand I sit at an empty table and gaze outside as the Badger slips away from the dock, then lower my head on the table for a nap. That’s when the fun begins. Over the next four hours I will struggle to find a way to describe the friendly, warm experience. Nearing Wisconsin, I conclude: The experience aboard the Badger closely resembles the atmosphere at the old Catskills, New York, resorts we were all reminded of in the movie “Dirty Dancing.”

The first clue arrives shortly after I sit down: bingo! An affable older gentleman with wire-rimmed glasses and neatly combed silver/white hair picks up a wireless microphone and stands at a podium. He purrs into the mike and welcomes players by reminding them to buy cards at a nearby counter. The room fills up fast with about 100 passengers anxious to start covering numbers. A mother-daughter duo lingers near me, looking for a place to sit. I wave them over and vacate the table. But I loiter for a while longer to watch this unexpected game play out. I came aboard expecting sleepy, bored passengers waiting silently to arrive in Wisconsin. Instead, I’m welcomed by announcements of “B-4” and “N-37” as youngsters and adults sit poised on the edge of their seats, ready to scream the name of the game. The announcer mixes in announcements of a trivia game to follow Bingo. He tells jokes: “What does a banana say when it answers the phone? Yell-ow!”

I leave the bingo session to walk through TV lounges, designated “quiet” rooms, gift shops, children’s game rooms, a museum, and a small theater. Children dart around me, engaged in a breathless scavenger hunt.

After a short nap in a lounge area near the bow I head outside and find a seat on a port-side balcony. Looking left and right, I can’t see land. To my left is the giant wake we’re leaving as we chug west toward Wisconsin. The bright sunshine creates millions of little bursts of light on the water’s surface, alternately blinding and hypnotizing me. I stretch out my legs, slouch back, and begin my second nap of the trip. The overall ferry experience has become a total decompression event for me. Thoughts of COVID have evaporated.

When I wake up a half-hour later, my head is tilted back and I’m staring at a sort of roof above me. After studying the structure and attached cables and metal arms, I realize it’s a lifeboat. In my post-nap daze my mind wanders back to the Titanic movie. Which character would I be if we started sinking? Would I be Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jack and avoid the rush to the lifeboats while heroically trying to save other passengers and my new love? Or would I be Billy Zane’s Caledon Hockley, rushing to the lifeboats and grabbing a child at the last minute, pretending to be a parent so I could join others on lifeboats? Just as I’m thinking about how Kate Winslet’s Rose would ensure my decision to be Jack, the captain unleashes a large blast on the horn. My daydream vaporizes. We’re approaching Wisconsin.

We slip into an inner harbor and begin a series of complicated maneuvers to dock in the city of Manitowac, population 35,000. It takes 10 minutes to back into the dock to position our ferry to lower the same ramp used to load vehicles in Michigan. Back in my car, I stop to take a few more pictures of the ship, and scoot off to my hotel.

Throngs of young adult baseball players and their families pile into the lobby as I wait to check in at my Holiday Inn. They’re here for a tournament. Some are already wearing cleats, click-clacking on the tile floor as they wait for parents to grab a room. Driving around exploring later that day, I find an unexpected treat: a Popeye’s Chicken restaurant. Takeout lunch in hand, I drive down to the water and scarf down the spicy chicken, mashed potatoes, and gravy while watching families play on a Lake Michigan beach.

Rifling through a Rand McNally Atlas in my room later that night, I make a bold decision to cut my trip short and head home early. I’m tired, yes, but, even more, emotionally exhausted by COVID news. I’d be in a better frame of mind at home with Elisa. The decision costs me hours of research and at least 10 phone calls to rearrange hotel reservations and choose a new route. My original plans called for me to head north through Wisconsin after the air show and then east across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, crossing the majestic Mackinac Bridge south into Mackinaw City. There I’d spend the night before taking a ferry to remote Mackinac Island at the northern edge of Lake Huron. I had then planned to drive south through the eastern side of Michigan and turn east back toward Cleveland and home. That leg of the trip represented two additional days.

Instead, I’d attend the annual Oshkosh air show as planned the next day — about an hour west of Manitowac — come back and spend a second night in Manitowac before motoring home southbound through Milwaukee and Chicago. At this point, shortly before going to bed, I was desperate to just get home by the fastest route. I couldn’t really explain to myself why, but that trip leg through upper Michigan seemed like a bad idea now.

Sharing my exploits

Social media didn’t exist when I first started dreaming of road trips in the 1960s. Neither did the internet. Heck, we were still dialing rotary telephones in Chicopee, Massachusetts. We watched TVs connected to rooftop antennas or the ubiquitous “rabbit ears” atop the set. And photography was a hard slog. You’d shoot some black and white photos on a box or 35mm camera, pull the film out, and dash down to the drugstore to get it developed. A week later, you’d pick up a hopefully fat envelope, open it, and rifle through 20–30 prints eager to see if you’d captured decent images or pictures of your foot or the floor. And the only way to share good pictures? You had copies printed … and mailed them.

Our digital age has changed all that. Not only do I love to read travel books, articles, essays, online blogs, and social media posts from others on the road, I’ve grown fond of sharing tales and photos of my own road trips with social media followers. This new hobby reached lofty levels in 2014 when I Facebooked, Twittered, Instagrammed, and even LinkedIned my long solo drive down U.S. Route 1. In a sense I had hundreds of imaginary travelers sitting with me as I bobbed and weaved over 2,400 miles down the East Coast. The number of my followers, commenters, and “likers” grew as my trip wore on. On some days, when I was late posting a daily summary, followers asked if anything was wrong. I reveled in the attention paid to my exploits. Selfies of myself in various locations drew raves, as did historical explanations of attractions, sights, and people I met. Some friends even came across my travelogue and invited me to visit or use their homes for a night.

Even better, the ongoing social media entries provided me with another record of my trip, capturing a mood or thought that didn’t appear in the notes I made each night or in my pictures. I’m sure there’s some scientific explanation for the pleasure one obtains from sharing stories of a trip. Maybe it’s as simple as virtually taking someone along with you for the ride and hoping they live, for the moment, vicariously through you. Social media makes it quick and easy. Even though I was inspired to write a book about the Route 1 trip, I still enjoy revisiting my social media posts from 2014. And that’s why I chose to do the same on what I came to call my “great western drive” during the summer of 2021.

I still made notes each night in the hotel room, but I wore out the screen of my iPhone and laptop crafting entertaining, witty posts, coupled with what I felt were thought-provoking photos. The reaction was the same. A small but growing group of online friends followed me each step of the way, sprinkling in likes, questions, and comments.

Next up in Chapter 3: Visiting the world’s biggest annual airshow, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and changing plans.

Chapter 3

Day 4; July 26, 2021

It starts as a whisper when you first begin learning how to fly airplanes. You hear it in flight school hallways and classrooms and in the cockpit during flying lessons. Almost every aviation magazine or book talks about it — a lot.

Oshkosh.

The word at first conjures up images of children’s clothes, especially overalls, made by a company out west. As a fledgling pilot you quickly learn it has a drastically different meaning. It’s the unofficial Mecca for all pilots. It’s THE annual celebration of all things aviation. And it takes place, of course, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

The Oshkosh air show is a massive event held by one of the largest and most respected aviation organizations: the Experimental Aircraft Association, or EAA. Founded over 70 years ago, the association focuses mostly on homebuilt, experimental airplanes — and the pilots who build and fly them. Over the years EAA has evolved to focus on most aspects of aviation, with the annual air show becoming the EAA centerpiece. Held on the grounds of Wittman Regional Airport, the gathering is also known as a fly-in event. About 10,000 airplanes land there in the days leading up to the affair and during the show, making the 1,400-acre Wittman facility for a short time the busiest airport in the world. Depending on the year and weather, more than half a million pilots and aviation enthusiasts attend the weeklong “Airventure” show. Airplanes of all sorts are on display or fly during the daily airshow. They range from small, propellor-driven acrobatic airplanes to fighter jets and the Concord supersonic plane. Manufacturers of aviation equipment display their products. Experts give seminars on flying. And the guest/speaker list often includes luminaries whose reputations extend well beyond aviation circles. The first men who landed on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission appeared one year. The man who broke the sound barrier, Chuck Yeager, has appeared often. The two pilots who conducted the first non-stop flight around the world, Burt Rutan and Jeana Yeager (no relation to the sound barrier guy), regularly give talks about flying the Voyager aircraft continuously for nine days without refueling.

Coming back to Oshkosh would represent a sort of homecoming for me, especially after the hard months of COVID. Also, Oshkosh was cancelled last year. I’ve been a private pilot for over 20 years and I love air shows.

I leave my hotel in Manitowac, Wisconsin, early, driving an hour west along U.S. Route 10 and then south for a short distance on Interstate 41 to Oshkosh. Exiting the highway, I meet bumper-to-bumper traffic. Instead of getting frustrated, I’m encouraged. The show, I think, must still be vibrant and popular if hordes of people are attending. I’m quickly ensnarled in an even larger jam trying to park, and end up parking about a 30-minute walk from the airshow grounds.

After looking at a few parked aircraft I walk to the northern end of the airfield, unfold my portable chair, and sit in a grassy area near where arriving airplanes are landing. I and fellow pilots who I’ve attended the event with over the years love to sit for a few hours and “grade” landings. I’m not disappointed. I see some airplanes wobble in and bounce a few times. Others gracefully touch down. A few small jets screech to a halt with reverse thrusters. The air traffic controllers do their usual expert job coordinating two or three aircraft landing at the same time.

A few attendees near me have portable radios tuned to the tower frequency. We eavesdrop on ground-air conversations. The transmissions are routine until one pilot directly above the airport gets confused and lost, forcing other pilots to make abrupt maneuvers to avoid him. He ignores commands from the tower and circles above both main runways. Controllers close the airport for 10 minutes while they try to get the pilot to listen. I cringe as I listen to the exchange, anticipating a mid-air collision. “I need you to talk to me … now!” one controller barks. The pilot finally responds, figures out the right pathway to land, and bobbles down to his assigned runway. Our few minutes of excitement are over. I continue to watch him as he taxis in. He’s an older man, and he looks upset and nervous.

At 2:30 p.m. the daily airshow begins. Finding a seat on the grass near the main north-south runway, I settle in and wait for the first act. It’s usually a nonstop, awe-inspiring demonstration of all sorts of aircraft and daring maneuvers: military jets and propeller-driven warbirds, acrobatic airplanes, harrowing formation flying, experimental aircraft, smoke-trailing stunt planes, helicopters, comedic airborne routines, and simulated explosions as restored warplanes dive low along the runway.

I see little of that today. What I witness is a three-hour procession of slow, propeller-driven airplanes doing the same maneuvers. I keep waiting for a blockbuster act. It doesn’t happen. I’m bored and disappointed. I leave early.

Later, as I make notes on the day, I chalk up the substandard experience to COVID. I had expected a rebirth of this famous show, but I failed to factor in booking and other scheduling problems during a pandemic.

It takes me a while to find my car in the parking lot, before driving east back to my hotel in Manitowac. Elisa and I have a long catch-up conversation on the phone while I drive. The hotel has provided a buffet dinner, but by the time I get there around 8 it’s picked over. I eat what I can, make a few final route notes in my room, and head off to sleep. Tomorrow will be a Herculean driving session. I’m heading home to upstate New York and I only want to make it back in two days.

Day 5: July 27, 2021

Interstate 43 guides me from Manitowac south, toward Milwaukee and then Chicago, where I’ll turn east toward home. It’s windy, with heavy gusts blowing west off Lake Michigan. I fight to keep my sleek little car in my lane.

The pandemic news of the day remains in my thoughts, since I scanned the news before leaving the hotel. My disposition swung from “I’m in a great mood after a good night’s sleep,” to flinging a copy of USA Today toward a trash can as I exit the lobby. One New York Times website headline sends me over the edge: “As Virus Cases Rise, Another Contagion Spreads Among the Vaccinated: Anger.”

Nearing Milwaukee, an hour south of Manitowac, I descend into a complex series of interchanges that conspire to funnel me away from picking up I-94 south toward Chicago. My eyes dart from the GPS on my dashboard to an open page in my Rand McNally to the blizzard of green highway signs. At about 9:30 a.m. I’m finally south of the Brew City on the next leg to Chicago. The winds are still howling off the lake, but I’m bathed in bright sunlight.

The towering skyscrapers of Chicago soon swallow me up. My highway darts in, around, above, and below parts of the city. Traffic slows to a standstill. It’s a regular Tuesday workday, but I mistakenly assumed traffic would be light since the pandemic is keeping most workers home.

A few miles south of Chicago, traffic remains thick but speeds up. An electronic roadside sign with an encouraging message appears: “Kick COVID to the curb. Get your shot.” It’s one of many I’ve seen over the last few days in Wisconsin and, now, in Illinois.

Just beyond the Illinois-Indiana border, a massive string of high-tension power lines rise on my right, along with electric-powered rail lines and stations. Mostly idle factories, mills, petroleum tanks, and dense neighborhoods crowd in on the highway. I’m approaching the city of Gary, population about 76,000. I’ve read about this hardscrabble, down-on-its-luck city over the years. It was once a steel-making center but has fallen on hard times, losing half its population since the 1960s. Searching on the internet later, I discover that unemployment and economic distress in Gary have led to one-third of all dwellings being left vacant.

***

I know little about the University of Notre Dame except for its football program and stature as a top-notch private university. The sprawling campus sits a short distance from I-90, about an hour past Gary and north of downtown South Bend. My visit today represents one of the few unplanned times I abandon the interstate to visit a site.

The campus is beautiful, quiet, and green. There’s a silent but powerful air of deep-thinking happening. Trees and other plants abound, sprinkled around hundreds of buildings. I park and walk around to take photos and a selfie in front of the gold dome atop the school’s Main Building. I see families visiting with their young-adult children. They all seem excited about being there. I overhear snippets of conversation about what students can do in this location or that one, or how close a dormitory is to a certain academic/classroom building.

Sitting on a bench later, I wonder what the future holds for these students. Will this fall bring a normal college experience for them? Will they arrive in South Bend amid one of the world’s most historic campuses, only to sit in on video classroom sessions in their dorm rooms until the “all clear” sounds from campus leaders? Or will they get there only to turn around and go home?

I stroll around the football stadium. Its brick walls soar skyward to form a bowl of sorts for those treasured Saturday afternoon fall sports celebrations. Knute Rockne’s statue stands on the north side of the stadium, reminding visitors of the historic successes of the program under his leadership: three national championships, the last one in 1930, and an overall record of 105 wins, 12 losses and five ties. Opposite the stadium stands the oft-photographed “Touchdown Jesus” mural on the Hesburgh Library. I take a few more photos and depart. Leaving, I discover Notre Dame has its own golf course. I imagine taking a break between classes to snag nine holes.

Eastbound again on I-90, I realize my gas tank is less than half full. I pull into a highway rest stop at Howe, Indiana, where my metaphor-infused encounter with the severed gas hose occurs. Nearing Toledo, Ohio, I pull into another rest stop to eat lunch: a sandwich I bought in Manitowac that morning. I have driven over 400 miles in seven hours since then, which seems like a lifetime ago. I open my trunk and sit on the back bumper of my car while I eat. I’m still reluctant to dine inside.

***

I slither through fleets of 18-wheelers and lane closures for construction as I complete my drive to Cleveland, where I’ll end my long trek with an overnight rest. I hadn’t planned to stay in this city a second night, but it fit nicely with the altered plans that would get me home earlier. And I’ve grown to like this older city on the shores of Lake Erie. Its blend of aging and modern architecture, bustling streets, pro sports teams, and history remind me of my favorite city, Boston.

I’m bone tired when I check into the last hotel on my trip, a modern high-rise Hampton Inn on busy East Ninth Street. The employees and most guests are masked — a welcome sight. One unmasked fellow rider on the elevator sneers at me and my mask and shakes his head. I simply stare at him until he breaks eye contact.

My destination for dinner is Mabel’s BBQ, tucked into pedestrian-only East Fourth Street. The narrow passage is adorned with lights strung across from buildings on each side, creating a warm, festive feeling. At Mabel’s I wait a few minutes for a table to become available outside. Over the next hour I eat some of the best chicken wings I’ve ever tasted. I wash them down with two glasses of a lighter micro-brew beer. My dinner is so big I can’t finish it. I box it and hand it to a homeless man sitting outside a bank between the restaurant and my hotel.

Before bed I scan a copy of USA Today and a few news websites. Bad move. Spread of the Delta variant continues to worsen. I’m upset and can’t go to bed right away. I surf some websites looking for a final location to visit on my last leg tomorrow. The destination I eventually choose is based on pure inspiration that I hope will lift my mood.

My sore butt and aching joints tell me I overdid it today. By the time I reached Cleveland I had driven over 520 miles in one day, often through gnarly, three-lane thickets of traffic. Still, I was one day closer to home.

Next week’s final chapter: Unexpected inspiration on the way home as I absorb the lessons of one of our country’s most epic rights battles that began in the 19th century. It’s not what you think.

Chapter 4, final leg

Day 6: July 28, 2021

With a full belly from my hotel’s buffet breakfast, I join a crowd outside the front lobby of a Cleveland hotel to reclaim my car from valet parking at about 8 a.m. The situation devolves into a frustrating experience. I’m one of a large crowd growing angry as we wait for our cars. There is only one person taking ticket stubs and dashing to a parking garage four blocks away. I talk to the father of one family with small children. He’s been there for a half hour. To make matters worse, he, his wife, and two young sons have an airplane to catch in two hours.

I’m in no real hurry, but I also have no interest in standing on a curb with my luggage for what I estimate will be over an hour. I make a snap decision. As the attendant jogs north to get another car I follow him. He turns to ask why I’m following. I say, “Hey, can I come with you and get my car? I’ll still tip you.” He nods yes. We walk to the garage together and take an elevator to the third floor where we find my car. A few minutes later, as I drive by the hotel enroute to I-90, I feel guilty when I see people still waiting for their cars, stomping about, and yelling.

I’m back on I-90 before 9 a.m., resuming my monotonous journey east along a road devoid of any character. Somewhere just short of the border with Pennsylvania, I spot a line of tractor-trailer trucks creeping in the other direction — as far as I can see. Tankers. Flat beds. The ubiquitous cargo trucks. Large trucks towing other trucks. Car carriers. Is this, I wonder to myself, part of the logistics/supply chain problems we’re all experiencing? Is my package from Amazon cooling its heels westbound on I-90, waiting for traffic to clear? Just as I start thinking I’m lucky my side of the highway is moving fast, we come to a near stop.

I make slow progress for the next three hours. In Erie, Pennsylvania, I pull off for lunch. Like Gary, Indiana, this fifth-largest city in Pennsylvania has fallen on hard times. Almost half its nearly 100,000 residents live at or below the poverty line. It’s also the site of an unusual geographic characteristic. Erie is in a small slice of a large state that fronts on Lake Erie. While Ohio to the west and New York to the east have massive lakefront mileage, it’s almost like the mapmakers who drew up the Pennsylvania border decided that the state needed to connect to part of the Lake Erie shore — no matter how small the portion of land was.

Finding a Subway sandwich shop, I enter and ask for my favorite: a roast beef sub. The clerk tells me Subway doesn’t sell roast beef. I’m shocked. I think he misunderstood me. I repeat my request; slower and a little louder. He says, “I heard you the first time. This Subway and others in the chain haven’t sold roast beef for a year or so. How about a sandwich with steak tips?” I think back to all the times I have bought a roast beef sub at Subway and shake my head. I walk out. Across the street is a local sub shop. They are only too happy to make me what I want. As I leave the parking lot to rejoin the highway, I keep thinking to myself, “Subway doesn’t sell roast beef?” At my next stop I conduct an internet search on the subject. I learn Subway stopped selling roast beef and rotisserie chicken in 2020 because they were the two most expensive items on the menu. Since my return, the sandwich chain has announced plans to bring back roast beef.

***

The night before I leave on the last leg of my trip, from Cleveland, I stare at my Rand McNally Road Atlas to try and find one last stop to cap off my adventure. For perhaps the 10th time since I left home, I think about how my trip was supposed to be a salve of sorts as the pandemic waned — but it turned into a bittersweet, mostly temporary respite from the latest blizzard of news on the plague. It wasn’t over.

As I trace I-90’s route through upstate New York, the name of a small town about halfway between Buffalo and Albany jumps out: Seneca Falls. The name sounds familiar. For years I’ve read that Seneca Falls’ downtown was believed to be the inspiration for the fictional town of Bedford Falls in Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” movie. No one connected to the movie has ever confirmed it, but the pictures of the setting do look a little like the town where George Bailey lived. There’s even a bridge across the Cayuga-Seneca Canal that resembles the span George was going to jump from before he was stopped by Clarence the Angel. There are other points of interest that locals and others cite — but hard evidence about connections to the movie is tough to find. One thing is true: Capra visited there in 1945. His movie was released a year later.

My desire to visit stems from a more important piece of Seneca Falls history. The town was the scene of one of the biggest steps forward in women’s rights: the 1848 Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention. One of the leading organizers was local resident Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose house still sits on a bluff overlooking the canal. She later met Susan B. Anthony. They became lifelong friends and fervent activists for women’s rights and the suffrage crusade that eventually led to women gaining the right to vote in 1920.

***

Seneca Falls sits south of I-90, west of Syracuse and near the northern edge of Cayuga Lake — one of upstate New York’s famous Finger Lakes. A canal/river connecting Cayuga with Seneca Lake to the west runs through the middle of what’s formally known as the Hamlet of Seneca Falls, within the Town of Seneca Falls. Population about 7,000. In its early days the community was an industrious mill and factory town, powered by access to nearby waterways. Today one of the largest businesses there is ITT Goulds Pumps. They make industrial pumps for businesses and industries across the world.

Downtown is quiet and typical for a small upstate community. The short main drag through town, Fall Street, is dominated by one- and two-story brick buildings housing businesses and apartments. There’s little traffic on the afternoon I pull in. I have a hard time finding it, but I finally locate the Women’s Rights National Park headquarters on Fall Street. Run by the U.S. National Park Service, it’s a small operation dedicated to preserving and displaying the important events that took place there in the mid-19th century. No one answers when I knock on the door. It’s closed.

But it’s not really what I want to see. I know Cady Stanton’s home is nearby. I pull up to it a few minutes later and stare at it, walking around for an hour. Like the downtown center, it remains closed due to COVID. Still, the inspiration I seek arises from my time spent looking at the home of the well-educated writer and brave activist.

The simple white/yellow farm house with green shutters and two stories rising on the north end sits near the corner of Washington and Seneca streets. A thick green lawn stretches to both roads. It’s eerily quiet on the day I visit. No one else is there. I close my eyes and try to imagine what Cady Stanton’s life was like in the 19th century and how this small home became the center of a worldwide movement. After she and her husband moved in in 1947, she began calling it the “center of the rebellion.”

Her first taste of the challenges facing women came in London in 1840. Along with her new husband, she was attending a global anti-slavery convention when she discovered that male delegates voted to prevent women from participating. Cady Stanton bonded with other women at the convention and began to formulate her feelings about women’s rights and how she could muster enthusiasm to change laws she felt were holding women back.

Cady Stanton’s efforts finally came to fruition in 1848 when she organized and, with help from close friends, conducted the first national women’s rights convention in her hometown. She wrote “The Declaration of Rights and Sentiments” after the event, sparking widespread controversy among many who were upset about the resolutions. The document contained such outlandish sentiments as, “He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education — all colleges being closed against her.” Modeled after the nation’s Declaration of Independence, her document was signed by 68 women and 32 men who attended the convention — including noted African-American social reformist and abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

What discussions, I wondered as I stood on Cady Stanton’s lawn, occurred in this house hundreds of miles from the metropolitan centers of the day as she braved insults and criticism from the mid-19th century male-dominated nation? She never feared speaking out. As I return to my car to find I-90 east, I decide that if someone courageous like her and her friends could emerge in the mid-1800s, we must still have similar visionaries and leaders among us today.

Standing against criticism, opposition, and hate, Cady Stanton and her cohort made the difficult, unselfish decision to risk their reputations and livelihoods in pursuit of a noble cause. She was doing something not for herself but to help others: to help make our nation and our world a better place for all. She stood 180 degrees from where most of our government and political leaders stand today: doing whatever it takes to stay in power.

***

The stop in Seneca Falls was good for my soul. I complete the final 180 miles of my drive home to Clifton Park in a more buoyant mood. The physical fatigue generated by two long days of driving from Wisconsin is drowned out by hope gained from the example of those 19th century women.

***

As I write this piece during the months after returning home, Delta starts to wane as people get more booster shots and vaccinations, and we remain outside for dining and other recreational pursuits. The ending of my first draft is upbeat, with a view toward a less bleak winter.

But Omicron arrives in October. The daily average of 80,000 new Delta cases, which fueled my frustration, balloons to over 800,000 new Omicron cases per day in mid-January.

While we’re certainly not back to the despair of a world without vaccines, it’s winter now, and my road trip options are limited. We’re all being tested again. I hope we have the strength, the resolve to beat the virus and smile once more. (Finished writing in January, 2022.)

###

Author’s note: Thanks for “riding along” with me. Please feel to comment or ask questions. I will post the entire narrative over on my website: markmarchand-upstateny.com if you want to read about the trip in its entirety. Have a similar road-trip/travel story? Please share!