By Mark Marchand

It’s near the end of another typical day for this man living on the east side of the Hudson River in the first half of the 20th century. After long hours in meetings, he propels himself and his wheelchair slowly toward the tiniest room on the first floor of his house. He rolls into the claustrophobic chamber and pulls an iron gate closed behind him. Turning himself and his chair around, he seizes a thick rope. He pulls it down slowly. His little “room” ascends. Together, he and his chair weigh more than 200 pounds, but he has grown used to the procedure and the force required to lift himself. Once he reaches the second floor, he stops pulling, unlocks another gate, and rolls into a long hallway that connects to bedrooms, bathrooms, and other quarters. He heads off to spend time with his family and rest, ready to repeat the exercise in reverse the next day.

Thus ends another long day in the life of a man who relied on a well-hidden, human-powered elevator to conceal his disability as he conducted work and meetings with far-reaching consequences across the planet. This was part of the daily life of Franklin Delano Roosevelt—our 32nd president—when he escaped the fishbowl of the White House for the sanctuary that was his beloved 49-room “Springwood” mansion. The home is situated in Hyde Park, N.Y. on a picturesque bluff overlooking the Hudson River north of Poughkeepsie. Visitors ranging from world leaders to politicians to cabinet members to business executives traveled to FDR’s home regularly to meet with the only U.S. president elected to four terms.

According to tour guides at the National Park Service site, FDR would often set up in his first-floor reading room for meetings, with his legs and wheelchair concealed by a blanket. Much of the public didn’t know that the man who suffered from polio at a young age had little use of his legs. When visitors left, guides say, FDR would complete paperwork and private meetings with staff and friends before quietly gliding over to the tiny elevator. Guests were unaware he couldn’t reach the second floor via stairs.

Despite his disability, there is little doubt about the powerful leadership the second Roosevelt to lead our country provided as we navigated the perilous waters of a depression, days of “infamy,” and a global war against dictators on two fronts. Some historians and citizens like me wonder how we might have survived as a democracy without him. When visitors on the same tour I attended in late 2022 asked the tour guide why FDR went to such lengths to conceal his paralysis, she explained that most people at the time thought physical handicaps affected cognitive ability. Thankfully today most are able to separate the two. Think about theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking. Unable to speak and restricted to his wheelchair, he paved the way to some of the most important physics breakthroughs of our time, including black holes.

Hyde Park and the FDR home, about 90 miles north of New York City and 70 miles south of Albany, is a treasure trove for those interested in early- to mid-twentieth century life. Visitors see for themselves how one man could serve as a bulwark against the forces of totalitarianism while ensconced in a private mansion sitting on a silent hill as the blue-gray waters of the Hudson chugged by a few hundred feet below.

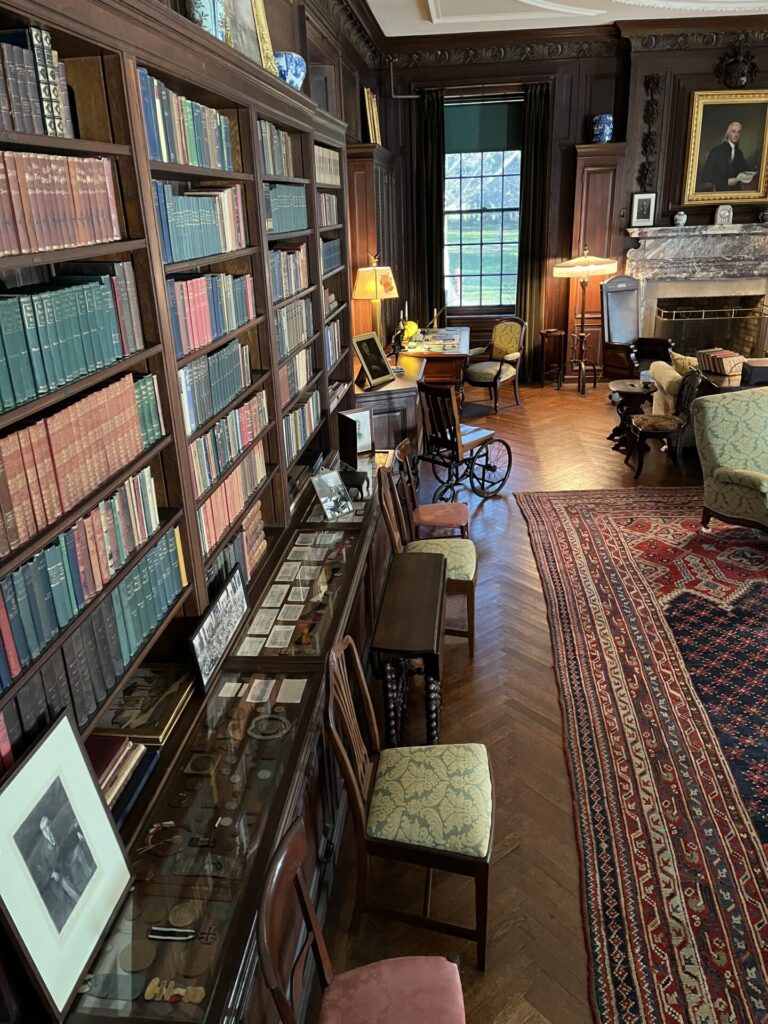

On the south side of the first floor is FDR’s reading room, where he conducted much of his business and worked on his large stamp collection. Towering walls of books, plush chairs and sofas, tables, and wall-mounted artwork are scattered about—lit by windows that stretch almost from floor to ceiling. A fireplace with a marble mantle stands ready to cast heat from the east side of the rectangular room. Off in one corner sits the custom-built wheelchair FDR designed himself. He hated the standard, clunky wheelchairs used in his day.

The rest of the 11-room first floor is made up of more “ceremonial” places: a sitting room, a formal dining room with a kitchen off to the side, a music room, and a grand center entrance.

The more-private second floor—where only overnight guests, close friends, and family were allowed— included FDR’s and Eleanor’s secluded bedrooms and bathrooms. The pair slept separately because the president needed to be moved or flipped every 90 minutes to two hours because of his disability. Otherwise, sores could develop on his body. Next to his bed are two phones. One, resting on a night table, is a common black set in use at the time. A second, wall-mounted handset linked directly to the White House. He could just pick up the phone and within seconds be talking to an operator at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Down the hall from FDR’s bedroom are several guest rooms. One large room was reserved for special guests, such as British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. For some of his World-War-II strategy sessions with FDR, Churchill journeyed up the Hudson to stay at Hyde Park. In all there are 29 rooms on Springwood’s second floor. The third floor has nine rooms, which were reserved mostly for Roosevelt children.

The 800-acre site also features walking trails, gardens, and FDR and Eleanor’s burial site. The National Park service has built a modern welcome center that helps visitors learn more about FDR before they walk south along a short path to the mansion. Springwood was expanded several times after FDR’s father James bought it in 1866. FDR was born there in 1882. In 1943, two years before he died in office, Roosevelt donated the building and surrounding acreage to the American people. Since 1945 the site has been maintained and run by the National Park Service.

The site is open year-round for history buffs and others looking to abandon the often-dry pages of history books for a realistic peak at how one of most important presidents and his family lived and worked.